| I confess. I was a religious addict. It took me about 10 years after leaving the Watch Tower to fit it into perspective. And the revelation came not primarily through logical reasoning, but my going through the last three years, the hardest ones of my life.

I lost a father, almost lost my mother, and lost a close friend of 13 years. I have never lost anyone really close to me in my life, and I am 58 years old, so this was a new shock; like being a virgin to the reality of life and death.

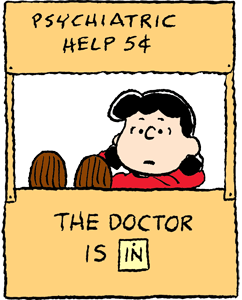

I sought help from a clinical psychiatrist and discovered I had some chemical problems in my system that was bringing me down. He helped me through three years of agony— I quit any form of medication or alcohol for 15 months, and was still as miserable as before. Then I asked him to test me for other things. I got some prescriptions that worked to get me back up and running.

As I pull out of this ghastly stage and return to normalcy, I have been able to understand it logically as well, but not through reading books. I logged all my own notes and deliberated on them. I began to understand the real reasons I have been such a religious zealot for large segments of my life. I was always extreme in my pursuance of the Watch Tower’s evangelism, always taking the hardest and most demanding tasks with gusto. I always felt confident as a Jehovah’s Witness. When I left in 1980, my conversion to evangelical religion just basically allowed me to continue to same zealotry, only as a born-again Christian.

Some people say the moment you doubt the truth, the devil comes in and steals your faith. I don’t believe that. Doubt has always been my salvation in keeping me safe from harm. Doubt is a PRIMAL, PROTECTIVE skill learned by mankind throughout his long history.

The problem is, that if your belief system is working so effectively, you are to afraid to examine it too closely for fear of having to struggle with cognitive dissonance all over again re: religion. The pain usually keeps the believer from even coming close to allowing hard thought on such things.

But in times of physical struggle and hardship, where you feel reduced to an animal, you are forced to think on such levels. This leaves you open enough to see clearly what is happening in the real world of our 5 senses, rather than looking to our pre-existent worldview of things. Instinct deciphers events, people, actions, and all life around you. Everything is much clearer than with having a concern for “invisible” or ethereal concepts.

I have striven to keep my senses balanced by having seen a mental health professional for several years. I still see him monthly. He helps me by giving me a view into the chemical, medical issues that I struggle with.

I do not consider that all or even most religious persons are necessarily addicted to religion. I was, and I found the following article to be of great help in giving an outline of how the process works. It has only been quoted in part; the full PDF file is available HERE .

I will offer my own personal comments in dark red text like this after each quote. I fell that this issue applies to a minority of people, but nevertheless a large enough number to aid society in understanding this phenomena. It also gives insight into terrorism cells and secretive political groups that take the place of the family and become one’s “larger,” more important family. The same dynamic is at work.

Religious Addiction and The Family System:

Implications for the Family Clinician

By THOMAS W. ROBERTS

My Comments: This paper explores how a religious belief system could be considered an addiction in the same way alcohol and drugs are addictions. Various aspects of substance addiction are reviewed in terms of their implications for addiction as religious belief systems. A systems perspective of religious addictive families reveals that addictive families tend to have rigid communication patterns. In addition, religious addictive families tend to have an imbalance in the religious and secular rituals which may be expressed through family life cycle transition dysfunctions. Treatment issues of religious addicts are multifaceted and represent a number of interdependent factors. Clinicians must view the religious addiction within the context which may extend beyond the family. The clinician views the religious addiction as symptomatic behavior which develops similarly to other family dysfunctions. In addition to reducing stress in the family life cycle, the clinician also may want to strengthen secular family rituals. Roberts Writes:

The adaptive role and function of religion for individuals is well documented in the extant literature from various disciplines (Allport, 1950; Berger, 1967; Tillich, 1952). The adaptive functions of religion include helping individuals adjust to both normal and unexpected change (Durkheim, 1961; O'Dea, 1970). Religion provides a sense of meaning to life (Franld, 1962; Weber, 1922) and the discovery of "the self' in relationship to "ultimate reality" or God (Tillich, 1952). In addition to aiding individual adjustment and finding meaning in life, religion tends to justify the social conformity of individuals (Berger & Luckman, 1967; O'Dea, 1970; Parsons, 1960). An individual experiences the integration of personal meaning and social conformity by the participation in religious rituals (O'Dea, 1970).

While most religious expressions are adaptive, the purpose of this paper is to explore how religious belief systems might be nonadaptive or addictive. In other words, can religious belief systems be addictive in the same way as alcohol and drugs can be addictive? Although little research exists on the relation of religion and addiction, a body of literature exists on each independently. This paper will draw inferences on this relation of religion and addiction and discuss the implications for family therapists in treating such families.

*Thomas W. Roberts, the Department of Home Economics and Family Living, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY 42101.

[Family Science Review, Vol. 2, No. 4, September, 1989 pp. 317-326]

...

RELIGIOUS BELIEF SYSTEMS AS AN ADDICTION

...

The following discussion outlines how religious addiction might be developed in the same way as a psychological addiction develops. First, substance addiction is linked to an escape from reason and painful experiences (Lenters, 1985). This addictive process is a numbing of the senses where the addict does not have to consciously face the painful existential questions of loss, disappointment, and ultimately death. Consequently, the addict slowly sinks into the existential void of nothingness that, paradoxically, is so desperately being avoided.

Religious belief systems can be used to easily escape from painful reality by relying on God to ease or lessen the burdens of life. In a similar way that the addict lacks confidence to deal with life adequately (Simmonds, 1977), the religious addict lacks confidence to face life squarely and uses the religious dogma to provide a shield to ward off this inadequacy (Peele & Brodsky, 1975). Although this escapism in religion may occur in any form, some religious belief systems tend to foster and encourage escapism. My fear of world events and the threat of mass nuclear destruction in the 60s led me to religion, for security.

...

Second, substance addiction is related to a dependency on alcohol and drugs (Lenters, 1985). Religious beliefs have been associated with greater dependence on external resources (Black & London, 1966; Fisher, 1964; Goldsen, Rosenberg, Williams, & Suchman, 1960; Simmonds, 1977). Addictive religion, therefore, could be seen as an unhealthy dependency on religious dogma, or a personal relationship with God (Allport, 1950). The issue in dependency is not so much independency versus dependency, but between addictive dependency on an outside source and dependency on a dynamic religious experience (Lenters, 1985). While the healthy religious adherent would see a dynamic balance between independence and dependence, a religious addict would polarize them (Simmonds, 1977). For example, a religious addict would place more emphasis on the external hand of God in life situations than on one's individual choices in determining those life situations (Fisher, 1964).

Roberts says, “Religious beliefs have been associated with greater dependence on external resources.” How true; but you risk never developing critical thought and seeing the more obvious reason why things are the way they are in real life. You no longer trust your primary instincts and are led by “logic” to sometimes go against them. This can be very dangerous.

Third, substance addiction has been described as an avoidance of taking moral responsibility for one's life (Lenters, 1985). The religious addict could be seen as failing to take moral responsibility for life decisions when he/she compulsively insists on giving God credit for achievements and successes. If God is responsible for every behavior, the religious addict neither accepts success nor failure as a consequence of freedom of choice (Simmonds, 1977). God is ultimately responsible for both good and evil.

I believed that if I did what I thought God wanted me to do, rather than to think things out first, I was being obedient. I was, to the “logic” of another person’s interpretation of life rather than being responsible enough to work it out on my own.

Fourth, addiction is characterized as continuous and exchangeable, i.e., an addict frequently changes or substitutes one addiction for another (Lenters, 1985). A person addicted to one substance may, in "curing" that addiction, become addicted to another even more debilitating drug. In terms of religious addiction, it would seem logical that addictive religious belief systems would be appealing to persons who have other addictions. For example, in the late 1960s, former hippies were converting to fundamental Christianity in large numbers. This turning to Christianity was referred to as the "Jesus Movement" (Simmonds, 1977). Researchers of the Jesus Movement have concluded that this switching to religion by former hippies was simply replacing one addiction for another (Peele & Brodsky, 1975; Simmonds, 1977). Since many adherents of the Jesus Movement appeared to be searching for meaning and security, the conversion to Jesus was only a different context to search for such meaning and security (Simmonds, 1977).

That was basically me; I was a Jesus Freak, a long-haired hippie that grew up in Orange County, Calif. I was nurtured under the wings of churches like Calvary Chapel and Vineyard Christian Fellowship. I wanted peace and love; not war.

Fifth, a major aspect of addiction is denial, i.e., refusing to admit one's addictive behavior and, consequently, forming rigid and non-critical cognitive patterns (Clinebell, 1963). Denial becomes the basis of the addict's self-system. The denial of alcoholism gives a false sense of control over one's life and relationships (Denzin, 1987). In religious addiction, one subsumes one's knowledge under the umbrella of a larger structure which may represent the particular beliefs of a charismatic leader (Simmonds, 1977; Peele & Brodsky, 1975). As Allport (1950) noted for unhealthy religion, the religious addict would be able to rationalize or moralize any questionable behavior through a belief system. Holding on to these beliefs in the face of circumstances or situations where relying on faith in God would be more appropriate, the religious addict never comes to grips with real experience (Simmonds, 1977). In the same way that the alcoholic denies the need for help (Denzin, 1987), the religious addict refuses to surrender his/her limited belief system (Simmonds, 1977).

Once fooled, twice is not so easy, at least for me. In my early Christian years of writing apologetics, I would still read all sorts of non-Christian or even anti-Christian literature; especially as an exit counselor. You learn how deception works in the same way that studying a card shark and his sleight-of-hand gives you insight into how easily we are fooled. So as a Christian I was not so addicted to a rigid set of beliefs. But for the first 8 years or so, I was still somewhat fanatical. It was my drug.

Sixth, substance addiction is related to the disintegration of relationships, particularly the family (Lenters, 1985). In religious addiction, there frequently can be a discontinuity between the generations (Markowitz, 1983). This discontinuity was quite apparent in the Jesus Movement where adolescents practiced a traditional form of religion that seemed to punctuate their separateness and alienation from their families rather than usher them into dialogue with family members (Markowitz, 1983). In families where one member tends to be a religious addict and other members are not, it can be assumed that a barrier exists in that family to reduce cohesion and unity.

I was lucky to escape problems on the family side. We were strong enough to go through it, in spite of me converting my mother, sister and brother-in-law. They left the Watchtower shortly after I did, and are now Christians and quite happy. My father never became a JW, but respected our wishes.

In summary, religious addiction can be viewed as an individual's attempt to deal with painful life experiences by escaping through supernatural means. Addictive religion could be related to an unhealthy reliance on religious dogma rather than taking responsibility for one's decisions. There is a tendency for the religious addict to have previous addictions and to have replaced them with religion. The religious addict is uncritical of his/her belief system and intolerable of those who question it. Finally, there is discontinuity in the religious addict's family relationships. Generations may be divided by these beliefs and the family may suffer from lack of cohesion.

How true this applies in the Jehovah’s Witnesses! The leadership is always trying to pit members against one another vying for their loyalty. “Will you obey God’s organization or listen to men??” they will say. By creating a massive guilt trip and fear of coming under attack fostered by the Witness publications and the Witnesses themselves, family members break their bonds with those closest to them to avoid the cognitive dissonance. Children never meet their grandparents, sons or daughters don’t see their parents for decades, and children are left out of the family will and kicked out of the house for not accepting this religious dogma. Jehovah’s Witnesses are amongst the worst of all religions for separating families. ...

This paper assumes that functional families are balanced in secular and religious rituals. Dysfunctional families are skewed toward either the secular or the religious end of the continuum. Religious addiction could be explained from this perspective as resulting from a skew in the family toward the religious end of the ritual continuum. This skew may take place as a result of failure to adjust to normal changes in the family life cycle. It also could result from and be perpetuated by a rigid and dysfunctional communication system. Religious addiction may be viewed as an attempted solution to stress in the system. As the stress increases in the family, one or more members move toward the religious end of the continuum to reduce stress. The increase in the religious ritual would decrease other more functional rituals. In systems terms, the attempted solution has become the problem (Haley, 1980).

Most outsiders looking in, due to their natural instincts, can tell a religious zealot from a balanced mind. Once a person recognizes what human nature is all about, and learns to balance it with any philosophical readings, one can survive without cognitive dissonance. You don’t even have to become an agnostic or atheist. But I have learned one thing that stands out above all—you must learn to judge things on your own before you accept the opinions of others. If we are to be judged, that is what we will be judged upon in the end. My philosophy is to “love people more and believe them less.” I keep my friends that way. ~

|