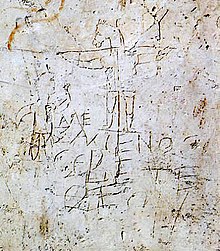

What was the graffiti artist intending when he/she scratched this cartoon like drawing on the wall of a building that served as a training school for imperial guards and personal attendants in the Imperial palace area of Rome. It is known as the Alexamenos graffito.

Our interest may focus on the crucified figure, but as a tracing of the drawing makes a little clearer - there's another figure of interest, a young male whose gestures indicate that he's praying, and the crudely written text says:

"Alexamenos, worship your god"

Both Christians and pagans worshipped with arm(s) extended and the most likely interpretation of this crude drawing is that the graffiti artist was ridiculing a young slave named Alexamenos, who had become a Christian (either before or after his enslavement), and at times was likely observed to be praying. Since for most Romans in the period the thought of an executed person being a powerful divinity was ridiculous, we can understand why bored guards or attendants, standing around without too much to do, may think and act as the graffiti indicates.

It all seems to make sense when we think of another item of graffiti, in the same complex (the next door building to be precise). It simply states (and its claimed to be by a different writer) Alexamenos fidelis, - That is, "Alexamenos is faithful."

Which came first cannot now be ascertained. Did Alexamenos write Alexamenos fidelis to describe his own spiritual goal and his associates drew that cartoon to amke fun of his aspiration, or was it the other way round.

I would imagine that being a slave and a Christian was not easy. Slaves had few rights, in fact if a young, handsome Christian, male slave had an owner who wished to have sex with him, the slave would have had little choice but to submit.

The Wikipedia entry seems quite accurate in its discussion. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexamenos_graffito

and an academic by the name of Dr Peter Keegan, at my university, in a book entitled 'Graffiti in Antiquity,' devotes about a page to it.

Whether we are Christian or not, the above graffiti gives us an insight into the minds of humans when this Asian religious concept was seeping into the western world. It's interesting to consider that at almost the same time as Christianity seeped into the Roman world, Buddhism seeped into the Chinese civilisation of the east.