________________

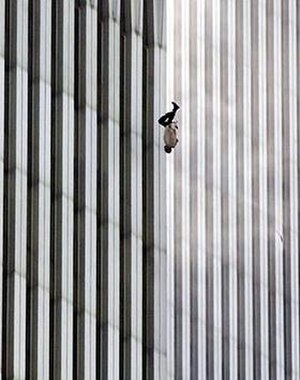

PORTRAIT of a MAN FALLING

(A short story by Terry Edwin Walstrom)

“Get out of here—this is

my father’s funeral; you don’t belong here; you

are a liar!”

________________

The woman’s face reflected the terrible pain—the

worst pain possible, to the point of breakdown. A thousand unanswered questions

had been washed from her eyes by the flow of many tears. She was bent forward

slightly—not from physical infirmity—but from the burden of suffering; a

suffering shared by her family.

A stranger was speaking to her and in his trembling

hand she caught sight of the photograph. There was pleading in his voice, a

quiet voice, and something in his eyes meant her no harm . . . so she had

dropped her gaze . . . and immediately collapsed.

The Editor and his staff listened quietly and a nodded

hesitatingly.

“I don’t know who this is, but it’s pretty clear he was somebody.”

Faces simply stared back

at him, wanted to listen, wanting to be convinced. Yet, at the same time, they

didn’t want to do the wrong thing in the wrong way at this—the worst of all possible wrong times.

“A carpenter reaches

for his hammer without thinking. I’m a photographer—I reached for my camera and

started taking pictures . . . that’s all it was . . . that’s all.”

Outside the office, a

bustle of activity bespoke controlled chaos. Like an anthill stomped upon, a

flurry of busy randomness had seized everyone in an invisible panic.

“I’d like to know.

But—it’s not my call. I don’t know what I’m asking, but maybe you all do.”

_______

The clear morning sky gave bright promise to the optimism of

a perfect day. It was the kind of day even the most jaded urban sophisticate

could glance at sideways and give up a begrudging smile of approval.

Traffic zipped, clotted, zoomed, or stalled to the dancing

red, yellow or green of the bedeviling signal lights along the avenues. Horns

honked, shoe leather patted concrete sidewalks in a pattern of big city

syncopation. Commuters and panhandlers went through the motions of survival at

both ends of the spectrum in a Darwinian paradise of tall, tall buildings and

crisp fall air.

It was 9:41.

The photographer had snatched his camera up and took off at

a brisk jog exactly to the spot where he suddenly froze. The carpenter reached for his hammer without thinking about it,

Richard Drew would later say to the others, just as he pointed his camera

upward toward the object which had caught his professional eye in the

viewfinder, and he began snapping instinctively. There was no right or wrong

about it—he snapped and his lens followed as it covered almost fifteen hundred

feet of vertical space, top to bottom in blink,

snap, blink, snap, blink of an eye.

_____

The theologian was asked to comment and he reluctantly

agreed.

The photograph laid out in front of him seemed to be all

stripes of black, gray and white with a random speck near the top. Doctor

Thompson adjusted his glasses and drew in a slow, deep breath as if bracing

himself for the worst. It took a few moments, like a strong drink swallowed too

fast, burning on the way down until. . .he removed his glasses again and

pinched the top of his nose with his eyes tightly squinted. The newspapers reprinted his comment.

"Perhaps the

most powerful image of despair at the beginning of the twenty-first century is

not found in art, or literature, or even popular music. It is found in a single

photograph."

______

Next day, on page 7 of the New York Times, the world stared at the photograph. Reaction came

immediately like the image in Edvard Munch’s painting, The Scream—an excruciating wail of anger, pain and denial swept

back upon the monsters who would publish such an image!

______

Official quote from the New York Medical Examiner’s office:

"A

'jumper' is somebody who goes to the office in the morning knowing that they

will commit suicide. These people were forced out by the smoke and flames or

blown out."

______

Only one man seemed driven to ask the questions nobody else

dared to ask. In his curiosity and determination, he questioned the wrong

people—showing them the terrible photograph. After all, he was guessing—and guessing

means getting it wrong as easily as getting it right. If the unknown was too

great a burden from him to bear, so too was it an unthinkable abomination—a blasphemy

for the Hernandez family at their father’s funeral. It was a sin to commit

suicide and it would send their beloved Norberto to the fires of hell! The

daughter lashed out with her bitter words and sent reporter Peter Cheney back

out into the street, stunned at the damage his questions had wrought.

The quest went forward.

Another possibility arose: Jonathan Briley, as the falling object in the

cursed picture, forever suspended upside down in mid-air, one improbable knee

bent, as the slim healthy man plummeted at maximum velocity toward infinity

below. Briley’s brother, Timothy

identified him by his clothes and shoes, as well as a ridiculous orange

undershirt barely visible as the white shirt ballooned out in the updraft of

the awful fall—he remembered his brother wearing it that morning.

His grief-stricken sister told the reporter, "When I first looked at the picture ...

and I saw it was a man—tall, slim—I said, 'If I didn't know any better, that

could be Jonathan.”’

Approximately 200 people fell or jumped that day. None was

deemed a “jumper,” but a victim of blunt force trauma in a murderous attack on

the World Trade Center.

The Hernandez family was again contacted and their minds put

at ease—not a minute too soon. Norberto’s daughters had been torn apart by

embittered consciences stricken by devout Catholic teaching. At last they could

accept he had simply been one victim—a martyr to be sure—among the 2,996 which

perished.

Of all the unspeakable horror of that day of infamy, the

photograph—a portrait of a man falling—became the focal point of unacceptable

remembrance.

Why?

None could or would accept the small measure of “choice”

implied in this man’s demise. The only

possible way the human mind could categorize the event was in terms of murder—not

elective suicide.

Few persons could wrap their mind around the idea of “postponement”

of the inevitable, in those few incredible minutes out in the open air—free of

smoke and terrible flames—the illogical logic of not wanting to be incinerated

in choking blackness and screams. . . Yet—it is so remarkably beautiful to come

away with a powerful sense of defiance and freedom in that last act—refusal to

accept a death chosen for them by brutal sadists on a feckless and twisted

Jihad.

To jump and sail free in an impossible escape on the wings of

God’s angels—or the simple purchase of five seconds more of precious life—who are

we to judge this man or the 200 others and affix blame or assign moral

verdicts?

In that moment of 9:41 a.m. September 11, 2001—there is an

eternal portrait of a man falling. He who may have greater courage than any

human has ever shown. 1,500 feet of flight on a most beautiful day with its

morning sun bright and clear, and a casual breeze softly caressing his flight

in a transcendent prayer of human dignity.

FREEDOM at any cost.