Are the Albanians modern Illyrians? Perhaps not the main reason for calling them Illyrians is because that nation used to occupy the area of modern day Albania in the past.

The Italians today number around 60 million not 40, I included Ukrainian among the Russian languages. Apparently the total figure doesn't add up to 3 billion but comes close to it.

Historical Linguistics

by dorayakii 49 Replies latest jw friends

-

greendawn

-

Pole

:: I included Ukrainian among the Russian languages.

Did you also include Dutch among the "English languages"? ;-)

Pole -

greendawn

Pole, as the speaker of a slavic language (Polish) you should know that Russian Byelorussian and Ukrainian are much closer to each other than English is to Dutch. They may be only marginally mutually intelligible but this is not the case with English and Dutch.

-

Pole

::Pole, as the speaker of a slavic language (Polish) you should know that Russian Byelorussian and Ukrainian are much closer to each other than English is to Dutch. They may be only marginally mutually intelligible but this is not the case with English and Dutch.

Interesting. You speak with a tone of authority, or maybe I'm just oversensitive, so maybe I can learn something ;-). Let's stick with Ukrainian vs. Russian, since I've never had much experience with Belorussian, and never made a point about it.

Methinks, you are confusing the fact that most Ukrainians know Russian with the supposed similarity between them. The easiest way to see my point is by asking a Russian living in St Peterburg if he/she understands much Ukrainian. In any case, there is nothing like the "Russian" languages in any serious synchronic classification that I'm aware of. Ukrainian by my subjective standards (and there are no conventions of comparing language similarity, especially between many language pairs) is much more similar to Polish (a West-Slavic laguage) than to Russian. If you know the languages I can give you some specific examples.

Pole -

greendawn

I an not a linguist, my only basis for saying that these two languages are marginally m.i. is what several Ukrainians told me, but as you say there are many dialects in each language and perhaps official Russian and official Ukrainian are not m.i. (based on Moscow and Kiev?) but the dialects spoken near the geographical border on the two sides are.

I would guestimate that Ukrainian being an East Slavic language is nearer to Russian than Polish which is West Slavic. -

Leolaia

dorayakii...Thanks for starting this thread! This was my actually my fascination when I went to high school...every recess I would be in the library doing more research, comparing cognates between languages. The regularity of the sound correspondences was quite intriguing...it showed that language change was not haphazard and chaotic but followed regular patterns. It also showed that the Society's chronology and beliefs about Hebrew (being the original language) could not be true.

Just to clarify one thing implicit in the comments to this thread, relatedness between languages is based not on which languages sound more alike (i.e. mutual intelligibility) but on which innovative differences are shared ... as indicative of a shared ancestry. It's not unlike the relationships between textual families. The various manuscripts of a given text (say, the Gospel of John) can be organized in an ancestral tree as the descendents of earlier texts that differ from each other by their innovative aspects. A copyist might make a scribal errors which would then be handed down by all descendents of that text. It's a matter of historical, derivational relationship.

Words in related languages don't even have to sound anything alike if regular patterns of sound change have altered the corresponding phonemes in sister languages beyond recognition. You can still tell that the languages are descendents of a single protolanguage by observing their predictable sound correspondences.

Consider the Malay word for pandanus: pandan (whence the English loanword). The Hawaiian word for "pandanus" is hala. Aside from the vowels, there is no obvious resemblance. Yet this is exactly the form you would expect. Malay /p/ = Hawaiian /h/ and Malay /d/ = Hawaiian /l/. As for the syllable final consonants, these are all deleted in the Oceanic languages, which adopt a strict syllable structure that always ends in a vowel. When we compare cognates between Malay and Hawaiian, we find very predictably that p = h and d = l:

Malay Hawaiian pandan 'pandanus' hala

daun 'leaf' lau

dua 'two' lua

empat 'four' eha:

api 'fire' ahi

panas 'hot' hana-, hahana

duduk 'sit, be quiet' lulu

ngipen 'tooth' (dial.) niho

penyu 'turtle' honu

Notice that the syllable-final consonants all drop in Hawaiian; hence, the lack of correspondence between the /m/ and /t/ of empat 'four'. Not all instances of /h/ in Hawaiian also correspond to a Malay /p/, for Malay /b/ also matches Hawaiian /h/ as well:

Malay Hawaiian buah 'fruit'

hua

batu 'stone' haku-, pohaku

bini 'woman' (dial.) wahine

balay 'house' (dial.) hale

This means that /b/ and /p/ (originally phonemically distinct in Proto-Austronesian as well) merged into a single consonant in Hawaiian (and all Polynesian languages as well). As for /l/, the example balay = hale also shows that Hawaiian /l/ corresponds to both Malay /d/ and /l/....indicating another phonemic merger in the development that led to Hawaiian. One might note other examples like langit 'sky' = lani, or lima 'five' = lima. Another merger can be found in the case of Hawaiian /n/, corresponding to both Malay /ng/ and /n/. A careful comparison of Austronesian languages shows that Malay is closest to the original Proto-Austronesian forms while Hawaiian is the most innovative...but shares some of its innovations with all the Oceanic languages (such as the loss of syllable-final consonants), some with only the Polynesian languages (such as p -> h sound change), and some are unique to only itself. This places Hawaiian quite precisely within the family of Austronesian languages. Some other sounds in Malay also predictably correspond to /zero/ in Hawaiian, such as /j/ in hujan 'rain' (= ua) and jalan 'road' (= ala). Finally, consider how Malay /t/ = Hawaiian /k/, and Malay /k/ = Hawaiian / ' /:

Malay Hawaiian kutu 'louse'

'uku

ikan 'fish' i'a

hutan 'inland forest' uka 'inland'

aku 'I' a'u, au 'I'

mata 'eye' maka

mati 'die' make

tangit 'cry, sound' kani

kita 'see' (dial.) 'ike

It's fascinating that languages separated for thousands for years still show systematic, unmistakable signs of common ancestry.

-

M.J.

Great read. Thanks! This one's a keeper.

Have you also looked into languages of the Far East? I don't know anything about those languages myself, but from my casual observance I'm struck by the phonetic difference (to my untrained ears at least) between Japanese and surrounding languages, such as Chinese. I tried searching for information once on a "family tree" of far Eastern languages but didn't find anything. But Leolaia's comment on "relatedness between languages...based not on which languages sound more alike" was an eye-opener.

-

dorayakii

Thanks Leolaia for your fascinating tables... I'm in my element here... I also used to spend time in the library comparing obscure Indo-European cognates. Now I spend most of my free time reading up about historico-linguistics in all the language families.

It also showed that the Society's chronology and beliefs about Hebrew (being the original language) could not be true.

Last time a JW told me that we'd all go back to speaking Hebrew in the New System, I introduced her to my Hebrew-speaking friend Omri, asked him to say a few things in his language to her... then later, I asked her... "would you really like to speak with those gutteral sounding uvular and pharyngeal fricatives for the rest of all eternity on a paradise earth?" ... She hesitated for a bit, then said that "it probably wasn't so harsh-sounding when Jehovah gave Adam and Eve Hebrew".

Words in related languages don't even have to sound anything alike if regular patterns of sound change have altered the corresponding phonemes in sister languages beyond recognition. You can still tell that the languages are descendents of a single protolanguage by observing their predictable sound correspondences.

Those examples you gave of Malay and Hawaiian are just superlatively fascinating...

Just for the laymen out there, here are some examples of the phonological changes of which Leolaia speaks. Here's a little quiz... Try and guess the cognates of the following French words. They have changed very little in most of the cases, but you still need to put your thinking cap on... Each of the three lines represent a different phonological change, 3 in all... and the very last word has had two big phonological changes... (Tip. When you've found the rule, try to ignore the vowels for the most part, they are much more fluid and subject to change. The answers are found at the very bottom of this post)...école, étude, écureuil, échelle, écharpe, écharde, écran, écumer, Ecosse

forêt, enquête, bête, fête, hâter, maître, plâtre, pâté, râper, conquête, huître, côte, hôtel, rôti

garderobe, Guillaume, garantie, guerrier, gauffre, guichet, guêpe

Its so rewarding to stare at a set of Indo-European words and then suddenly see them come into sharp focus when you notice the English cognates. Particularly when its a leter that was present in an older Anglo-Saxon form of the word or if its a silent letter. eg. "know" being related to the German "kennen", Greek "gnostic", Latin "cognoscere" which gave birth to Italian "conoscere" and French "connaître". "Connaître" and "know" are not even recognisable as cognates, but history tells us differently.

It blows your mind when you first learn that Sanskrit "jna", Urdu and Punjabi "janna", Russian "znat" all meaning "to know" are directly related to their English cognate "know"...... or when you trace the etymological roots of all the numbers from 1 to 10 in all of the Indo-European languages.

Have you also looked into languages of the Far East? I don't know anything about those languages myself, but from my casual observance I'm struck by the phonetic difference (to my untrained ears at least) between Japanese and surrounding languages, such as Chinese.

I'm currently studying Japanese at higher further level at university, so I can give you a bit of background.

The reason why Japanese bears little resemblance to Chinese dialects (including Mandarin, Cantonese and Wu), is because Japanese is not in the Sino-Tibetan langugae-family but in the Japonic family which includes Japanese and its sister languages all confined to the Japanese islands. Although most Westerners believe the two languages to be related, ancient Chinese and ancient Japanese could not have been further apart from each other linguistically.

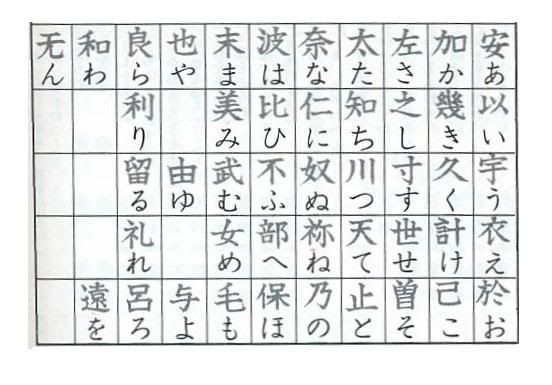

Many factors cause people to believe the two langugaes are related. First of all, in the 5th Century, during the Chinese Han dynasty, Buddhist monks brought Chinese texts back to Japan. They began to use a writing system called "man'yogana" in which 48 Chinese characters (kaisho) were stripped of their ancient meaning and used only for their sound. The first Japanese writing system of 48 (now 46) syllabically phonetic letters called "hiragana" was devised from writing these "kaisho" in the cursive Chinese "s ô sho" method of calligraphy. In the folowing table, the complex Chinese kaisho are on the top, and the simple Japanese hiragana on the bottom.

Because of the influence of the "Central Kingdom" (China), using the original "kaisho" letters was viewed as intellectual, educated and masculine... whereas most poetry done by women in that period, was written in the cursive "hiragana". Soon however, male authors also came to write literature using hiragana.

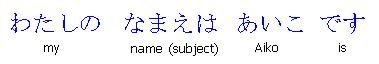

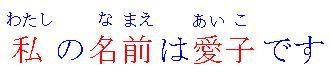

Unfortunately, the beautifully phonetic hiragana "alphabet" (or more accurately "syllabary") never conquered the whole of the Japanese writing system. Today, the Japanese use a mixture of the 46 hiragana and 1944 "kanji", which are chinese characters used for meaning with limited pronunciation value. Hence, a simple phrase like "watashi-no namae-ha aiko desu" (meaning "my name is Aiko") would normally be written like this (with a mixture of meaning-carrying Chinese characters in red and phonetic Japanese hiragana in blue):

instead of uni-phonetically (hiragana-only) like this.

wa-ta-shi no na-ma-e ha a-i-ko de-su (my name is Aiko)

I have often thought of petitioning the Japanese government to do away with the 1944 kanji and to start writing in hiragana-only. However, they would probably call me a "baka-yarou gaijin" (stupid b*stard foreigner) and tell me that if i'm too lazy to learn 1944 characters, i'm luck i don't have to learn the 6,500 characters in Chinese instead (or 13,500 traditional chinese characters). 1944 doesn't seem so many to learn afterall.

The advantages of the hiragana-only approach are that instead of learing the 1944 meaning-bearing kanji that Japanese borrowed from the Chinese, you only have to remember 46 simple, cursive, phonetic letters to be able to write anything in Japanese... not much different from learning our 26 simple Roman letters of the alphabet.

But on the other hand, there is an advantage to the kanji-hiragana mixture. A Japanese person can see straight away that the meaning of "Aiko", is "love-child", even if you don't know how to pronounce it. Also the multitude of homonyms (words with different meanings but he same pronunciation such as "eight / ate" or "bye / by / buy"... or the dreaded "their / they're / there") can be very simply differentiated from each other because they are written with different characters.

Japanese learners often have difficulty reading kanji-hiragana texts, but surprisingly, Japanese often have slight trouble understanding hiragana-only texts, due to the absence of spaces between words in Japanese writing and the fact that they're used to reading with the meaning of the kanji jumping out at them...

I have already learnt about 500 of the 1944 Chinese characters in Japanese, but for about 200 of them, i know only what they mean, not how to pronounce them. If I see them in a book or a newspaper, I may still be able to understand the passage, but would not be able to read it out loud. In addition to the difficulty that foreign learners experience, many children of high-school age have not yet learnt all of the kanji. For this reason, in many childrens' school books, there are often mini-hiragana (called "furigana") above words written in kanji, that explain how to pronounce them.

Here is the same sentence written in the kanji-hiragana mixture, with furigana over the kanji for ease of pronunciation (as you can see Aiko is one of my favourite names:

wa-ta-shi no na-ma-e ha a-i-ko de-su (my name is Aiko)

Many kanji have two or more readings. For example the character for the word water, has a native Japanese pronunciation "mizu" and a sino-japanese pronunciation "sui" which was modeled on "shui" the pronunciation in the ancient Han dynasty when the character was first borrowed.

Japanese

Sino-Japanese

Han Chinese

Meaning

mizu

sui

shui

water

okane

kin

chin

money

yama

san

shan

mountain

kuru

rai

lai

to come

ookii

tai

ta

big

katana

to

tao

sword

kuchi

ko

k'ou

mouth

kotoba

gen

yen

word

toki

ji

shih

time

kuruma

sha

ch'e

wagon, car

hayashi

rin

lin

woods

kodomo

shi, su

szu

child

toshi

nen

nien

year

kokoro

shin

hsin

heart

hanasu

wa

hua

to speak

otoko

dan

nan

man

Further differences between Chinese and Japanese is that Japanese has no tones. The bane of the Chinese-learners existence is that the meaning often completely changes if you say "mà" (to scold) in a falling tone, as opposed to "má"(hemp) in a rising tone , "m àá" (horse) in a rising then falling tone, or "maa" (mother) in a level tone... (This Chinese idiosyncracy has produced the famous Mandarin phrase "maama mà màá de má ma?" which means, "Is Mother scolding the horse's hemp?")

Thankfully, Japanese has no tones.

Another difference between the two is that the Chinese dialects are also very monosyllabic and each character/syllable usually represents only one word, one idea. The sino-Japanese roots follow suit in monosyllability. Pure Japanese roots on the other hand, contain many polysyllabic morphemes.

Notice though, that the Sino-Japanese readings in the table above are in this case very similar to the Han Chinese readings. As China was at one point the dominant power in the Orient, many techincal words (of the time) borrow from the lexis of this ancient form of Chinese. Very similar to how we have looked back to Latin and Greek roots, in order to formulate words like "television", or "microscope". The word for "telephone" in Japanese is "den-wa" meaning "lightning-speech" and is *quite* similar to the Chinese "tien-hua", which uses the same characters.

However, since the 1940s, with the popularity of English in the present day technological field, many many words for technical objects are borrowed from English, "terebi" (television), "konpyuuta" (computer), "paso-kon" (PC, "personal computer"), "rabo" (laboratory), krejitto kaado (credit card) and even "kounfreikusu" (cornflakes)... Japanese has even borrowed from French, Portuguese and German: "randebuu" (rendez-vous - appointment), pan (pão - bread) and arubaito (arbeit - work).

As if Japanese didn't have enough alphabets, these foreign words are written either in "romaji" an adaptation of our roman letters and spelled as they are written above... or in a jazzy and sharp script called "katakana", which mirrors hiragana in its 46 letters.

Because my screen name "Dorayakii", is a jazzy, flashy, made-up name to Japanese people (from "dorayaki", my favourite japanese dessert), if i wanted to say "my name is Dorayakii" i would have to write the name in katakana like this (with the katakana in green):

wa-ta-shi no na-ma-e ha do-ra-ya-ki-i de-su (my name is Dorayakii)

Japanese has shown just as much willingness as English has to adapt to changes, to incorporate new vocabulary and to innovate with both gramar and lexis. It is a beautifully written, poetically spoken language that deserves to be kept alive.

These are the answers to the French-English "cognate quiz"...

Please note that these rules are only specific to these cognates, so don't thin that you can decipher the whole language just by looking at phonological and orthographical changes in cognates.school, study, squrirrel, scale, scarf. scard, screen, skim, Scotland...... (the general rule is "é" is represented as "s" in English)

forest, inquest, beast, feast, haste, master, plaster, pasty, rasp, conquest, oyster, coast, hostel, roast...... (the general rule is an "s" is placed after the vowel where there is the diacritic ^ )

wardrobe, William, waranty, warrior, waffle, wicket, wasp...... (the general rule here is "g" or "gu" is represented by "w" in English)

-

M.J.

Wow, thanks for providing such extensive info on Japanese. Japanese is actually a real interest of mine. I hope to learn it some day. This answers many of the questions I had. I always sensed that pronunciation in Japanese was closer to Spanish than to Chinese, oddly enough (I can speak Spanish).

Oh as for imported words, don't forget Ehoba

When I get home from work I'll definitely pour over the details of your post as it is fascinating to me.

-

dorayakii

Oh as for imported words, don't forget Ehoba

Haha, pleeease don't...

The funny thing is, they use a calque of "Jehovah God", and call him, "Ehoba-Kami", which is just as strange to Japanese ears as "Jehovah-God" is to English. Here are a few other imported words and calques that the "Ehoba no Shonin" use:

Iesu Kurisuto (Jesus Christ)

Ehoba no Shonin (Jehovah's Witnesses)

Soromon no Uta (Song of Solomon)

Erusaremu (Jerusalem)

Matai, Maruko, Ruka, Yohane (Mathhew, Mark, Luke, John)

Seisho Shinsekai Yaku (Bible New-world Translation)

Monominoto, Seisho, Sasshi Kyokai (Watchtower, Bible, Leaflet Association)

The first Watchtower organisation in Japan was incorporated in 1938 and was called "Todaisha", meaning "The Lighthouse Company".