Anyone read Candida Moss book how early Christians invented

A story of martydom. The Romans did not terget, hunt or

massacre Jesus' followers says a historian of the early church.

If it's true or not, I don't know but it is a interesting read.

by jam 18 Replies latest jw friends

Anyone read Candida Moss book how early Christians invented

A story of martydom. The Romans did not terget, hunt or

massacre Jesus' followers says a historian of the early church.

If it's true or not, I don't know but it is a interesting read.

that would demolish the biggest argument of Wt writers for their claim to veracity of the resurrection (and by extension their doctrines).

Wt claims that the Early Christians would not have been willing to suffer all this torture (see the 'talking to Tiger topic') IF

the resurrection was not real, really believable.

Roman records shows, during the only concerted anti-Christian

Roman campaign, under the emperor Diocletian between 303 and 306,

Christians were expelled from public offices. Their churches, such as

the one in Nicomedia, across the street from the imperial palace,

were destroyed.

Well if the Christians were holding high offices in the first place and

had built their church "in the emperor's own front yard". they could

hardly have been in hiding away in the catacombs before Diocletian

edicts against them..

prologs: Good point "demolish the biggest argument of the WT".

Constantine was the first emperor to stop Christian persecutions and to legalise Christianity along with all the other cults in the Roman Empire.

In February 313, Constantine met with Licinius in Milan, where they developed the Edict of Milan. The edict stated that Christians should be allowed to follow the faith without oppression. This removed penalties for professing Christianity, under which many had been martyred previously, and returned confiscated Church property. The edict protected from religious persecution not only Christians but all religions, allowing anyone to worship whichever deity they chose. A similar edict had been issued in 311 by Galerius, then senior emperor of the Tetrarchy; Galerius' edict granted Christians the right to practise their religion but did not restore any property to them. The Edict of Milan included several clauses which stated that all confiscated churches would be returned as well as other provisions for previously persecuted Christians.

Scholars debate whether Constantine adopted his mother St. Helena's Christianity in his youth, or whether he adopted it gradually over the course of his life. Constantine would retain the title of pontifex maximus until his death, a title emperors bore as heads of the pagan priesthood, as would his Christian successors on to Gratian (r. 375–83). According to Christian writers, Constantine was over 40 when he finally declared himself a Christian, writing to Christians to make clear that he believed he owed his successes to the protection of the Christian High God alone. Throughout his rule, Constantine supported the Church financially, built basilicas, granted privileges to clergy (e.g. exemption from certain taxes), promoted Christians to high office, and returned property confiscated during the Diocletianic persecution. His most famous building projects include the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and Old Saint Peter's Basilica.

However, Constantine certainly did not patronize Christianity alone. After gaining victory in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge , a triumphal arch—the Arch of Constantine—was built to celebrate his triumph. The arch is decorated with images of the goddess Victoria. At the time of its dedication, sacrifices to gods like Apollo, Diana, and Hercules were made. Absent from the Arch are any depictions of Christian symbolism. However, as the Arch was commissioned by the Senate, the absence of Christian symbols may reflect the role of the Curia at the time as a pagan redoubt.

Later in 321, Constantine instructed that Christians and non-Christians should be united in observing the venerable day of the sun, referring to the sun-worship that Aurelian had established as an official cult. Furthermore, and long after his oft alleged conversion to Christianity, Constantine's coinage continued to carry the symbols of the sun. Even after the pagan gods had disappeared from the coinage, Christian symbols appeared only as Constantine's personal attributes: the chi rho between his hands or on his labarum, but never on the coin itself. Even when Constantine dedicated the new capital of Constantinople, which became the seat of Byzantine Christianity for a millennium, he did so wearing the Apollonian sun-rayed Diadem; no Christian symbols were present at this dedication.

The reign of Constantine established a precedent for the position of the emperor as having great influence and ultimate regulatory authority within the religious discussions involving the early Christian councils of that time, e.g., most notably the dispute over Arianism, and the nature of God. Constantine himself disliked the risks to societal stability that religious disputes and controversies brought with them, preferring where possible to establish an orthodoxy. One way in which Constantine used his influence over the early Church councils was to seek to establish a consensus over the oft debated and argued issue over the nature of God.

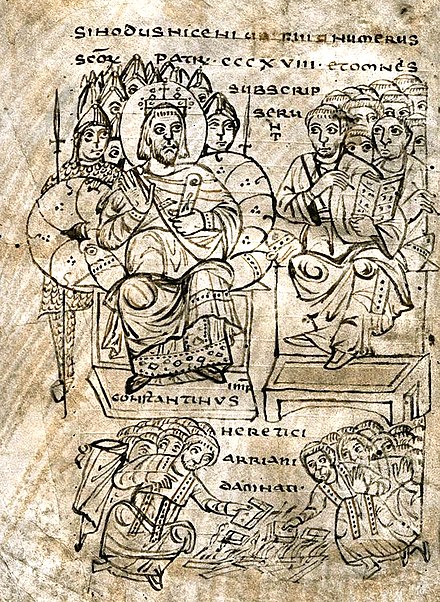

Most notably, from 313–316 bishops in North Africa struggled with other Christian bishops who had been ordained by Donatus in opposition to Caecilian. The African bishops could not come to terms and the Donatists asked Constantine to act as a judge in the dispute. Three regional Church councils and another trial before Constantine all ruled against Donatus and the Donatism movement in North Africa. In 317 Constantine issued an edict to confiscate Donatist church property and to send Donatist clergy into exile. [218] More significantly, in 325 he summoned the Council of Nicaea, effectively the first Ecumenical Council (unless the Council of Jerusalem is so classified). The Council of Nicaea is most known for its dealing with Arianism and for instituting the Nicene Creed.

Constantine enforced the prohibition of the First Council of Nicaea against celebrating the Lord's Supper on the day before the Jewish Passover (14 Nisan) (see Quartodecimanism and Easter controversy). This marked a definite break of Christianity from the Judaic tradition. From then on the Roman Julian Calendar, a solar calendar, was given precedence over the lunar Hebrew Calendar among the Christian churches of the Roman Empire.

Constantine made new laws regarding the Jews. They were forbidden to own Christian slaves or to circumcise their slaves.

Thanks Finkeistein. I always wondered, how can people set and watch

their neighbors or friends being torn apart by lions. And then i think

about Nazi Germany. The difference, the people in Germany did not

witness the death of 6 million Jews, their neighbors and friends.

Christians were a motley crue of different ideas and beliefs before Constatine so why would they be persecuted, so this may be correct Jam. They christians themselves became the persecuters after their legalization.

Jam, may be you and I will turn away when real death scenes are shown on the screen, but people have and do watch eagerly live gory spectacles, witness the very public execution in the public places. and

there is footage of local spectators watching as Einsatzgruppen, and local helpers shot row after row of Jewish people in deep trenches, in the Ukraine, in Poland.

would the first century, the second,-- have been better?

Main article: Diocletian Persecution "Faithful Unto Death" by Herbert Schmalz

The persecutions culminated with Diocletian and Galerius at the end of the third and beginning of the 4th century. The Great Persecution is considered the largest. Beginning with a series of four edicts banning Christian practices and ordering the imprisonment of Christian clergy, the persecution intensified until all Christians in the empire were commanded to sacrifice to the gods or face immediate execution. Over 20,000 Christians are thought to have died during Diocletian's reign. However, as Diocletian zealously persecuted Christians in the Eastern part of the empire, his co-emperors in the West did not follow the edicts and so Christians in Gaul, Spain, and Britannia were virtually unmolested.

This persecution lasted, until Constantine I came to power in 313 and legalized Christianity. It was not until Theodosius I in the later 4th century that Christianity would become the official religion of the Empire. Between these two events Julian II temporarily restored the traditional Roman religion and established broad religious tolerance renewing Pagan and Christian hostilities.

Martyrs were considered uniquely exemplary of the Christian faith, and few early saints were not also martyrs.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia states that "Ancient, medieval and early modern hagiographers were inclined to exaggerate the number of martyrs. Since the title of martyr is the highest title to which a Christian can aspire, this tendency is natural". Estimates of Christians killed for religious reasons before the year 313 vary greatly, depending on the scholar quoted, from a high of almost 100,000 to a low of 10,000.

The first documented case of imperially supervised persecution of the Christians in the Roman Empire begins with Nero . In 64 AD, a great fire broke out in Rome, destroying portions of the city and economically devastating the Roman population. Some people suspected Nero himself as the arsonist, as Suetonius reported, claiming he played the lyre and sang the 'Sack of Ilium' during the fires. In his Annals, Tacitus (who wrote that Nero was in Antium at the time of the fire's outbreak), stated that "to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians (or Chrestians) [ 11 ] by the populace" (Tacit. Annals XV, see Tacitus on Jesus). Suetonius, later to the period, does not mention any persecution after the fire, but in a previous paragraph unrelated to the fire, mentions punishments inflicted on Christians, defined as men following a new and malefic superstition. Suetonius however does not specify the reasons for the punishment, he just lists the fact together with other abuses put down by Nero.

By the mid-2nd century, mobs could be found willing to throw stones at Christians, and they might be mobilized by rival sects. The Persecution in Lyon was preceded by mob violence, including assaults, robberies and stonings (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 5.1.7).

Further state persecutions were desultory until the 3rd century, though Tertullian's Apologeticus of 197 was ostensibly written in defense of persecuted Christians and addressed to Roman governors. The "edict of Septimius Severus" familiar in Christian history is doubted by some secular historians to have existed outside Christian martyrology.

The first documentable Empire-wide persecution took place under Maximinus Thrax, though only the clergy were sought out. It was not until Decius during the mid-century that a persecution of Christian laity across the Empire took place. Christian sources aver that a decree was issued requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent to a testimonial of allegiance to the Emperor and the established order. Decius authorized roving commissions visiting the cities and villages to supervise the execution of the sacrifices and to deliver written certificates to all citizens who performed them. Christians were often given opportunities to avoid further punishment by publicly offering sacrifices or burning incense to Roman gods, and were accused by the Romans of impiety when they refused. Refusal was punished by arrest, imprisonment, torture, and executions. Christians fled to safe havens in the countryside and some purchased their certificates, called libelli. Several councils held at Carthage debated the extent to which the community should accept these lapsed Christians.

Some early Christians sought out and welcomed martyrdom. Roman authorities tried hard to avoid Christians because they "goaded, chided, belittled and insulted the crowds until they demanded their death." According to Droge and Tabor, "in 185 the proconsul of Asia, Arrius Antoninus, was approached by a group of Christians demanding to be executed. The proconsul obliged some of them and then sent the rest away, saying that if they wanted to kill themselves there was plenty of rope available or cliffs they could jump off." Such seeking after death is found in Tertullian's Scorpiace or in the letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch but was certainly not the only view of martyrdom in the Christian church. Both Polycarp and Cyprian, bishops in Smyrna and Carthage respectively, attempted to avoid martyrdom.