This is one I know from Catechism school back in Catholic school days. But make of it what you will (and my memory might be foggy--I am old).

The confusion about the words for some comes from people thinking that Koine Greek was the spoken language of the day in which the New Testament events took place.

They were not. The events you are reading about took place in three other languages: Aramaic, Latin, and only rarely Liturgical Hebrew. (The Jews did not speak Hebrew in the Second Temple period. Note when Jesus prayed Psalm 22 in Litugical Hebrew from the cross and Jewish people don't know what he is saying because they speak Aramaic as recorded at Mark 13:34-35.)

Koine Greek, in which the Christian texts are written in, is the lingua franca of the day (much like Latin is to us). Rome was the ruiling power back then, but Greece had previously conquered the world and Hellenized much of the culture before. Because of this, forms of the Greek language, especially Classical Greek, were commonly read and understood by the most learned around the civilized world.

But to get something out to the most common folk--and since people spoke so many different tongues at the time--which Latin was becoming the most spoken due to Rome's influence--a "common" or vernacular form of Greek was used as the lingua franca to communicate with everyone who could read or understand Greek. Koine Greek was created to do this.

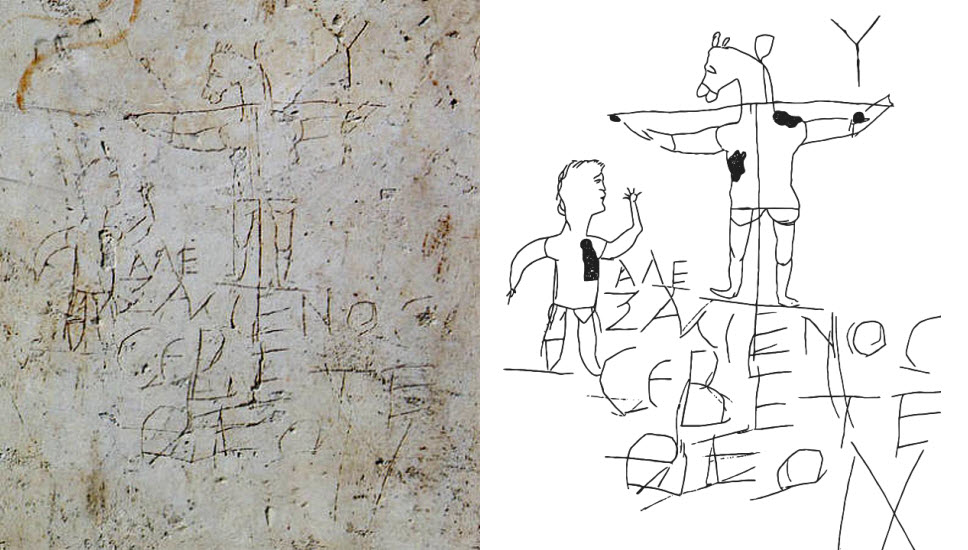

But there were new inventions that the Greek language could not explain. The "cross," for example, was one of them, as it had not been invented during the time of Alexander the Great when the Greek language was spread throughout the world. The cross was a torture device created by the Roman army--and that was to come later down the road after Alexander.

While the Greeks under Alexander did indeed impale victims, the Romans found the practice too quick of a punishment. They wanted to torture those they punished to warn the people under their rule not to break Roman laws. By means of experiment, the Romans learned that by merely adding a small platform for the feet to stand on and a bar to stretch out the arms to expand the lungs, one could cause the victim to slowly asphyxiate over a period of several days instead of die in a few short hours. They would tie or nail their victims in place, totally nude, forcing them to have to urinate and release their bowels in public as they slowly died before friends, family, and their neighbors, with a sign posted above listing their crime. Their lungs would slowly fill with fluid over the course of this period, and they would literally drown because they could not support the weight on the tiny platform under their feet. If it took too long for them to die, they would break the victims legs, causing them to drown even quicker in the collected lung fluid. The invention was a Roman "improvement" on the single pale of the Greeks.

But when translating the Latin word "crux" into Greek, there was no exact word for it. So they used "stauros" (pale) and sometimes "xylon" (tree/wood). But there may be a reason why they used "xylon" if you note when the word begins to appear in the New Testament and you match it with the writings of the Church Fathers.

According to the Fathers, the Cross of Jesus was, theologically speaking, the Tree of Life because Jesus was the "Second Adam." (1 Co 15:45-58) When the soldiers pierced him and "blood and water" flowed forth, this was symbolic of life-giving rivers in the Garden of Eden. (John 19:33-34; compare John chapter 4 and Genesis 2:10-14) Mary being present was the "woman" spoken of in Genesis 3:15, and unlike Eve who in a sense said "no" to God by partaking of the wrong tree, Mary said "yes" by doing God's will and being the faithful Mother and disciple of Jesus, even to the point of being at the cross when others left his side, in a sense replacing Eve. So a dead tree becomes a Tree that supplies the world Life--according to what the Church Fathers write (and there's a lot of this, so you will likely spend a lot of time looking up these texts, so have fun).

Anyway, after Jesus dies and is resurrected, you will note in the New Testament, the word used for the cross by Peter (and the author of Luke who previously employed "stauros") is "xylon." In fact, Peter uses it exclusively afterwards in the Bible after the crucifixion and resurrection.--Acts 5:30, 10:39, 1 Pe 2:24.

And it seems to be theological, as Luke, who is the writer of the Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, switches from "starous" to "xylon" after the resurrection, putting the word "tree" also in Paul's mouth in his discourse to the Jews.--Acts 13:29.

The Church Fathers mention that the ties here are not only with the "Tree of Life" theology of the early Church, but that the theology comes from the symbolism it drew from readings of the Alexandrine Septuagint, which it viewed as the official Old Testament in those days. Not only did the texts of hanging a dead criminal upon a "tree" stand out clearly as symbol of Christ to them, but so did the many texts of a "tree" being life-giving and a home for God's creations. The symbolism was not lost on the author of the Book of Revelation.-- Re 2:7; 22:2, 14, 19.

Of course, this may be considered just hogwash, but I thought it was interesting because there is a pattern, and the Church Fathers did come before the canon of New Testament texts became, well before it was settled.

And it is true that people tend to think that people were talking in Greek, when in reality the Jews were talking in Aramaic and the Romans in Latin. They were not nailing people to anything that called a "stauros" or a "xylon" because they were not "talking" in Koine Greek.