Web-reference: http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index.php/archives/05/2012/new-research-opens-the-door-on-early-american-migration NEW RESEARCH OPENS THE DOOR ON EARLY AMERICAN MIGRATION Article created on Sunday, May 20, 2012

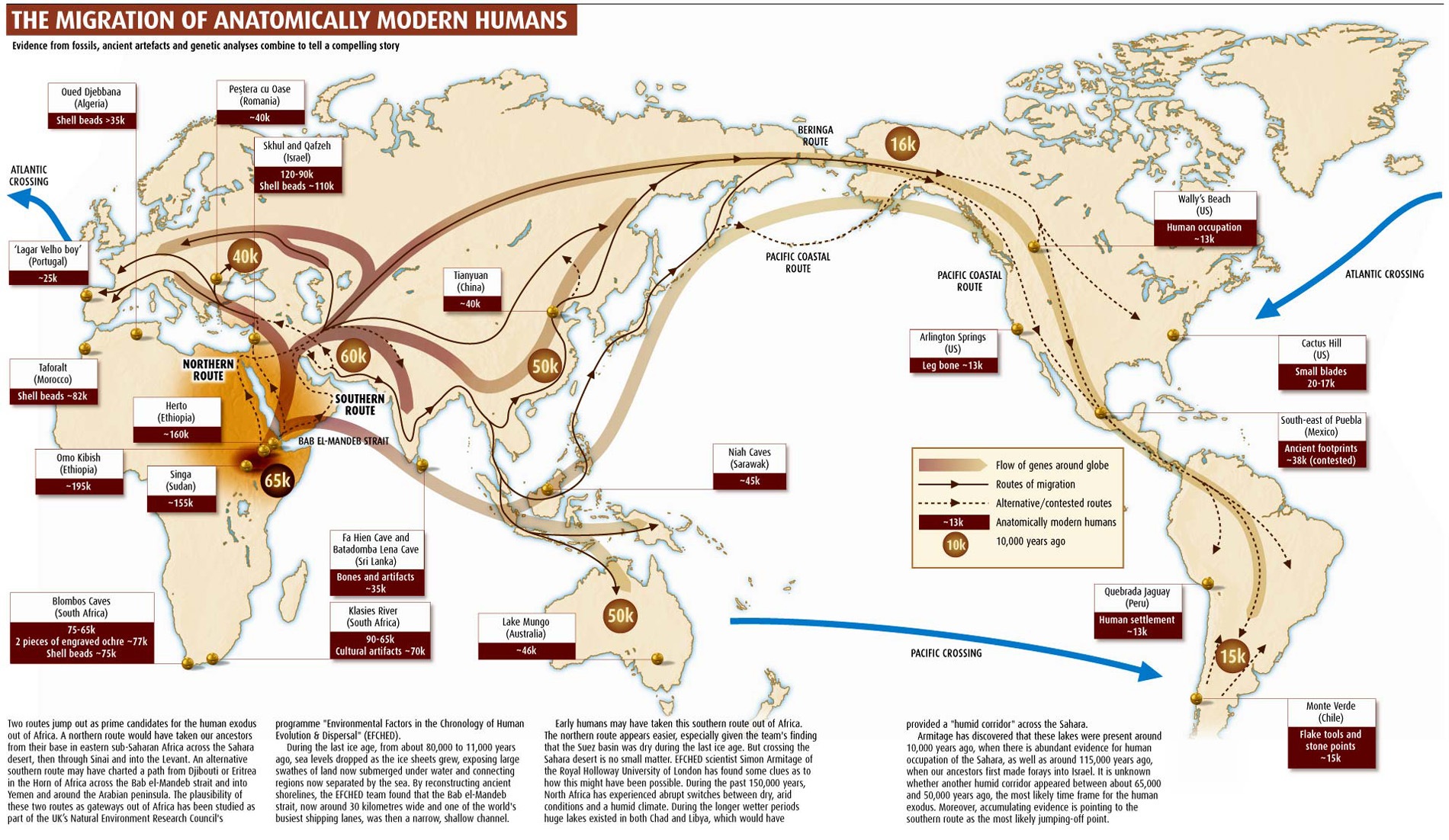

Studies carried out by the University of Pennsylvania and National Geographic’s Genographic Project have revealed new information regarding the migration patterns of the first humans to settle the Americas. They have managed to identify the historical relationships among various groups of Native American and First Nations peoples and present the first clear evidence of the genetic impact of the groups’ cultural practices. A detailed examination of genetic history For many of these populations, this is the first time their genetics have been analysed to this level of detail on a population scale. One study, published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, focuses on the Haida and Tlingitcommunities of south-eastern Alaska. The other study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, considers the genetic histories of three groups that live in the Northwest Territories of Canada. Establishing shared markers in the DNA of people living in the circum-arctic region, the team of scientists uncovered evidence of interactions among the tribes during the last several thousand years. The researchers used these clues to determine how humans migrated to and settled in North America as long as 20,000 years ago, after crossing the land bridge from today’s Russia, an area known as Beringia. The data suggest that Canadian Eskimoan- and Athapaskan-speaking populations are genetically distinct from one another and that the formation of these groups was the result of two population expansions that occurred after the initial movement of people into the Americas. In addition, the population history of Athapaskan speakers is complex, with the Tlicho being distinct from other Athapaskan groups. “These studies inform our understanding of the initial peopling process in the Americas, what happened after people moved through and who remained behind in Beringia,” said author Theodore Schurr, an associate professor in Penn’s Department of Anthropology and the Genographic Project principal investigator for North America. Both papers also confirm theories that linguists had posited, based on analyses of spoken languages, about population divisions among circum-arctic populations. The shared cultures of Haida and Tlingit The first paper focused on the Haida and Tlingit tribes, which have similar material cultures such as potlatch, or rituals of feasting, totemic motifs and a type of social organization that is based on matrilineal clans. Using cheek-swab DNA samples, the analyses confirmed that the two tribes — although they possessed some similarities in their mitochondrial DNA makeup — were quite distinct from one another. Comparing the DNA from the Tlingit and Haida with samples from other circumarctic groups further suggested that the Haida had been relatively isolated for a significant period of time. This isolation had already been suspected by linguists, who have questioned whether the Haida language belonged in the Na-Dene language family, which encompasses Tlingit, Eyak and Athapaskan languages. In the clan system of Haida and Tlingit peoples, children inherit the clan status — and territory — of their mothers. Each clan is divided in two moieties, or social groups, for example the Eagle and the Raven in the Tlingit tribe. Traditionally, a person from the Raven clan married someone from the Eagle clan and vice versa. “Part of what we were interested in testing was whether we could see clear genetic evidence of that social practice in these groups,” Schurr said. “In fact, we could, demonstrating the importance of culture in moulding human genetic diversity.” Genetic histories of the Inuvialuit, the Gwich’in and the Tlicho The other paper expands this view of circumarctic peoples to closely consider the genetic histories of three groups that live in the Northwest Territories: the Inuvialuit, the Gwich’in and the Tlicho. The Inuivialuit language belongs to the Eskimo-Aleut language family, while the Gwich’in and Tlicho speak languages belonging to the Na-Dene family and the Athapaskan subgroup. In this study, the researchers analysed 100 individual mutations and 19 short stretches of DNA from all individuals sampled, obtaining the highest-resolution Y chromosome data ever from these groups. Inuit Totem, Sitka, Alaska. Image: Seth Anderson (Flickr, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0) The team’s results indicate several new genetic markers that define previously unknown branches of the family tree of circumarctic groups. One marker, found in the Inuvialuit but not the other two groups, suggests that this group arose from an Arctic migration event somewhere between 4,000 and 8,000 years ago, separate from the migration that gave rise to many of the speakers of the Na-Dene language group. “If we’re correct, [this lineage] was present across the entire Arctic and in Beringia,” Schurr said. “This means it traces a separate expansion of Eskimo-Aleut-speaking peoples across this region.” Many of the native groups who have participated in both studies are also enthusiastic collaborators, Schurr said. “What we find fits very nicely with their own reckoning of ancestry and descent and with their other historical records. We’ve gotten a lot of support from these communities.” “Perhaps the most extraordinary finding to come out of these two studies is the way the traditional stories and the linguistic patterns correlate with the genetic data,” Spencer Wells, Genographic Project director and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence, said. “Genetics complements our understanding of history but doesn’t replace other components of group identity.” Sources: National Geographic & University of Pennsylvania More information: - Theodore G. Schurr, Matthew C. Dulik, Amanda C. Owings, Sergey I. Zhadanov, Jill B. Gaieski, Miguel G. Vilar, Judy Ramos, Mary Beth Moss, Francis Natkong. Clan, language, and migration history has shaped genetic diversity in Haida and Tlingit populations from Southeast Alaska. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2012; DOI:10.1002/ajpa.22068

- M. C. Dulik, A. C. Owings, J. B. Gaieski, M. G. Vilar, A. Andre, C. Lennie, M. A. Mackenzie, I. Kritsch, S. Snowshoe, R. Wright, J. Martin, N. Gibson, T. D. Andrews, T. G. Schurr, S. Adhikarla, C. J. Adler, E. Balanovska, O. Balanovsky, J. Bertranpetit, A. C. Clarke, D. Comas, A. Cooper, C. S. I. Der Sarkissian, A. GaneshPrasad, W. Haak, M. Haber, A. Hobbs, A. Javed, L. Jin, M. E. Kaplan, S. Li, B. Martinez-Cruz, E. A. Matisoo-Smith, M. Mele, N. C. Merchant, R. J. Mitchell, L. Parida, R. Pitchappan, D. E. Platt, L. Quintana-Murci, C. Renfrew, D. R. Lacerda, A. K. Royyuru, F. R. Santos, H. Soodyall, D. F. Soria Hernanz, P. Swamikrishnan, C. Tyler-Smith, A. V. Santhakumari, P. P. Vieira, R. S. Wells, P. A. Zalloua, J. S. Ziegle. Y-chromosome analysis reveals genetic divergence and new founding native lineages in Athapaskan- and Eskimoan-speaking populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2012; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1118760109

The Genographic Project seeks to chart new knowledge about the migratory history of the human species and answer age-old questions surrounding the genetic diversity of humanity. The project is a nonprofit, multi-year, global research partnership of National Geographic and IBM with field support by the Waitt Family Foundation. At the core of the project is a global consortium of 11 regional scientific teams following an ethical and scientific framework and who are responsible for sample collection and analysis in their respective regions. Members of the public can participate in the Genographic Project by purchasing a public participation kit from the Genographic website (www.nationalgeographic.com/genographic), where they can also choose to donate their genetic results to the expanding database. Sales of the kits help fund research and support a Legacy Fund for indigenous and traditional peoples’ community-led language revitalization and cultural projects. |