Ignore the LDS stuff but I haven't got time to weed it out. Apologies for the layout as well. Shrugs.

Fiery-Flying Serpents

He sent fiery-flying serpents among them and after they were bitten, he prepared a way that they might be healed. (1 Ne. 17:41 1 Ne. 17:41 )

In Num. 21:6 Num. 21:6 , where the incident referred to is related, Moses says the Lord sent "fiery serpents"-not "fiery-flying"-among the people. The same expression occurs in Deut. 8:15 Deut. 8:15 . It is clear, therefore, that Nephi did not copy this from Moses.

Isaiah (14:29) likens King Hezekiah to (comp. 2 Kgs. 18:8 2 Kgs. 18:8 ) a "fiery-flying serpent," and Nephi was familiar with this portion of the Old Testament. (See 2 Ne. 24:1 2 Ne. 24 ) The inference is that he followed Isaiah, in his version of the occurrence, adopting the term used by the prophet as the one that furnishes the more detailed explanation.

Moses was commanded to make a "fiery serpent" and so he made a "serpent of brass" and raised it upon a pole. (Num. 21:8 Num. 21:8 , Num. 21:9 9) This brass serpent was preserved for perhaps seven centuries and was finally broken up by King Hezekiah, because the people burnt incense to it. Isaiah had seen that brazen serpent before it was destroyed, and he must have had some reason for using the term "flying" in addition to "fiery" or "brazen," in comparing Hezekiah to it. Is it not probable that it was the image of a serpent with wings, such as the Egyptians made?

In Egypt, where the Israelites as a nation were cradled and where Moses had received his first education, the sacred serpent was the symbol of divine power and wisdom. When Egyptians would express the conception that Egypt was "God's country" enjoying his special care and protection, they drew a picture of two flying serpents of the uroeus species, one wearing the crown of upper, and the other that of lower Egypt. In this picture divine power, wisdom, and protection were visualized, very much as we symbolize national power and other admirable characteristics, as we perceive them with the eye of patriotism, by an Eagle or a Lion, or a Dragon, etc. What has been called the Egyptian national emblem was the solar disc between two serpents, the latter probably representing the eastern and western horizon of the sky, where the sun apparently rises and sets. Wings are extending on either side.

The image of the sacred serpent occurs as one of the ornaments of most of the Egyptian divine personages. It is part of the crowns of Osiris, Isis, and Horus. When Moses, therefore, was commanded to make a seraph, he was, in all probability, instructed to make not an imitation of the venomous reptile crawling in the dust, but of the glorious personages serving before the thrones of God-the seraphs which Isaiah and other prophets saw in visions; the same personages which were represented in golden statues upon the mercy seat of the Ark of the Covenants, and embroidered upon the curtains in the most holy place, also called cherubim.

This view is supported by strong considerations.

Just what kind of reptiles the serpents that the Lord sent among the Israelites were is not known. Moses calls them "seraphim serpents" (hanechashim haseraphim), either because their poison was very deadly, or because they were God's messengers of death. But it is certain that the brazen serpent, which Isaiah seems to have referred to as a "flying" serpent, was a type of our Lord who is the source and giver of life; for so we read in John 3:14 John 3:14-15 , where our Lord Himself says:

"And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life."

That was the great lesson of the serpent which Moses lifted up in the wilderness. Made of brass, the image must have appeared as fire in the rays of the desert sun, and suspended from a pole it was properly likened to a flying animal.

The prophecy in Isa. 14:29 Isa. 14:29 helps us to understand the symbolism of the winged serpent. "Him that, smote, thee" is understood to refer to Uzziah, king of Judah, who "smote" the Philistines. (2 Chr. 26:6 1 Chr. 26:6 , 2 Chr. 26:7 7 7) That "rod" was broken by his death, and during the reign of Ahaz, the Philistines invaded Judah and took possession of some of the southern cities. Isaiah, therefore, tells them that they had better not rejoice, because of this success. It was only temporary, for out of the "broken rod," should come forth a "cockatrice" or "adder," referring to Hezekiah, the son of Ahaz, and great-grandson of Uzziah, a more terrible enemy than Uzziah. (2 Kgs. 18:8 2 Kgs. 18:8 )

But Dr. Clarke informs us (Com. on Isa. 14:29 Isa. 14:29 ) that the Targum renders the 29th and 30th verses thus: "For, from the sons of Jesse shall come forth the Messiah; and his works among you shall be as the flying serpent. And the poor of the people shall he feed, and the humble shall dwell with famine, and the remnant of thy people shall he slay."

This may be, as Dr. Clarke remarks, a "singular" interpretation, but it shows that the Hebrew conception of the reign of the Messiah is expressed by the image of a "flying" or "winged" serpent. The word used by Isa. 14:29 Isa. 14:29 is saraph which may be familiar to us in its plural form seraphim which we read "seraphs," and understand to mean a high order of angels attending the Lord. (Isa. 6:2 Isa. 6:2 , Isa. 6:6 6) They are represented as having six wings; such is the swiftness of their service. Winds are angels. (Heb. 1:7 Heb. 1:7 ) They are princes, nobles, in heaven. But, says Gesenius, "If any one chooses to follow the Hebrew usus loquendi, in which seraph is serpent, he may indeed here render it [seraphim] by winged serpents; since the serpent both among the ancient Hebrews and Egyptians was the symbol of wisdom and of the healing art. See Num. 21:8 Num. 21:8 ; 2 Kgs. 18:4 2 Kgs. 18:4 .

The serpent appears in every conceivable form in ancient Egyptian theology. Sometimes it has a human body. It is a symbol of majesty, and as such has wings and a crown. Winged serpents represented the divine protectors of upper and lower Egypt. (Light on the Land of the Sphinx, Chapt. 9, by H. Forbes Witherby, London, 1896)

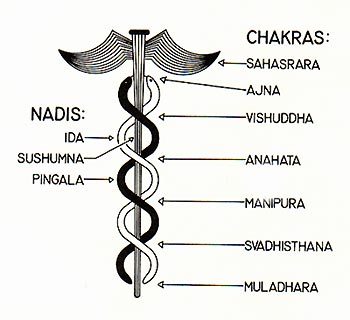

Now, the strange fact is that the winged serpent, or the feathered serpent, plays a prominent part also in the religious concepts of the American Indians, and in their traditions. Among the ancient Mexicans, one of the divinities was known as "the feathered" or "plumed serpent," Quetzalcoatl, which name corresponds to the "flying serpent" of the Hebrews. Quetzalcoatl among the Mexicans was what the brazen serpent was to the Hebrews-the representative of the healing, life-giving power, as Esculapius was among the Phoenicians.

Among the Nahuas Quetzalcoatl was revered as a God. At Cholula he was considered the chief God, somewhat like Jehovah among the Hebrews. He was regarded as the son of Camaxtli, the protector of hunters and fishers, but probably the same as the Pachacamac, the Creator, of the Peruvians.

But Quetzalcoatl also became a man. As such he was born of Chimalma, the wife of Camaxtli, who conceived him miraculously. He taught men the arts of civilization, and preached morality, penitence, and peace.

As a man he visited Cholula, remaining there for twenty years. He taught the people to work in silver, prohibited blood sacrifices, and showed them the way to happiness through virtue and peace. After his mission was finished, he left for the sea shore, where he bid his companions farewell and promised that, some time, in the future he would return.

One of the opponents of Quetzalcoatl was Tezcatlipoca, a personage of divine origin and great power, but evil, bent upon bringing calamities and misfortunes upon the people.

The ecclesiastical officer next in rank to the pontiff, or high priest, was called Quetzalcoatl, in honor of the great national hero, and there were, therefore, a great many quetzalcoatls, and the probability is that the traditions relating to the divine reformer and his successors have been so mixed as to preclude the possibility of a clear and perfect understanding of what the ancient Mexicans really did believe, but what is here stated seems to be the essence of it.

The Mexicans kept a sacred fire burning perpetually, as did the Hebrews, and by that fire they waited patiently for the return of Quetzalcoatl. It is claimed that the Pueblo Indians had a similar custom in their kivas, for a similar reason.

"Amongst the semi-civilized nations of America, from Mexico southward, as also amongst many nations of the Old World, the serpent was a prominent religions symbol, beneath which was concealed the profoundest significance. Under many of its aspects it coincided with the sun, or was the symbol of the Supreme Divinity of the heathens, of which the sun was one of the most obvious emblems. In the instance before us, the plumed, sacred serpent of the aborigines was artfully depicted so as to combine both symbols in one." (E.G. Squire, Nicaragua, Vol. 1, p. 406.)