aqwsed12345

JoinedPosts by aqwsed12345

-

113

Luke 23:43 the NWT

by Ade inluke 23:43 - and jesus said to him, "positively i say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.

nwt places comma here , giving a totally different meaning to the verse.

now the average jw uses this to back their doctrine and it seems in itself virtually impossible to reason with them on it.

-

-

113

Luke 23:43 the NWT

by Ade inluke 23:43 - and jesus said to him, "positively i say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.

nwt places comma here , giving a totally different meaning to the verse.

now the average jw uses this to back their doctrine and it seems in itself virtually impossible to reason with them on it.

-

aqwsed12345

@Earnest

I quote from HERE:

The Watchtower's final defense is that a handful of other translations and the Curetonian Syriac also place "today" with "Amen I say to you" and not the following expression. It must first be stressed this argument from authority does not prove that the comma is misplaced in the majority of translations. The NWT may not be unique in its punctuation of this verse, but that fact does not establish its correctness.

The two English versions mentioned by the Watchtower are Rotherham and Lamsa. Rotherham's translation of Luke 23:43 may well be influenced by E.W. Bullinger, whom Rotherham knew and respected (Reminiscenses of JB Rotherham, Chapter 10.). Whether Bullinger's views were well-founded will be examined later in this essay. In any event, Rotherham's translation has not been recognized by Bible scholars of any theological persuasion as being authoritative. The translation of George Lamsa may have once been punctuated as the WT claims, but all editions I have seen place the comma in the traditional location. Furthermore, if Lamsa's Aramaic source was the Peshitta (Bruce Metzger expressed some doubt on this point*), the English translations of the Peshitta by James Murdock and J.W. Etheridge also place the comma before "Today."

- * George Lamsa, L-A-M-S-A, who in the 1940s persuaded a reputable publisher of the Bible in Philadelphia, the Winston Publishing Company, to issue his absolute fraud, of 'the Bible translated from the original Aramaic.' Absolutely a money getter, and nothing else. He said that 'the whole of the New Testament was written in Aramaic,' and he 'translates it from the Aramaic,' but he never would show anybody the manuscripts that he translated from. Secondly, why would Paul write in Aramaic, let us say, to the people of Galatia? They didn't know any more Aramaic than people in Charlestown or Princeton know Aramaic.�

- The Curetonian Syriac

Regarding the Curetonian Syriac, it is true that it places "today" with "Amen I tell you," but it is problematic to use this fact in support of a correct understanding of the original Greek text. The Old Syriac Gospels are preserved in two manuscripts: The Sinaitic and the Curetonian. Both contain Luke 23:43. The Sinaitic most likely predates the Curetonian by about 100 years. Burkitt posits that the Sinaitic represents a more accurate Syriac text, while the Curetonian was corrected from a later Greek text (one containing a number of spurious passages) (Burkitt, Crawford, Evangelion Da-Mepharreshe, Vol 2, Gorgias Press, 2003.). Luke 23:43 in the Sinaitic text reads:

Jesus said unto him, Verily I say unto thee, To day shalt thou be with me in Paradise."7

The Syriac Peshitta agrees with the Sinaitic text, against the Curetonian, as do the Syriac Diatessaron, the Sahidic Coptic, and a number of manuscripts of the Old Latin. Ephrem, a 4th century commentator on the Syriac Gospels, quotes this verse three times, each time omitting "today." However, he says, "Our Lord shortened His distant liberalities and gave a near promise, To-day and not at the End....Thus through a robber was Paradise opened." (Burkitt, op cit., p. 304. Burkitt also quotes Barsalibi (d. 1171) who admits that "some" place "today" with "Amen I tell you," but does not approve of this reading.)

The Curetonian manuscript is thus of no value in determining the correct punctuation of Luke 23:43. It cannot be demonstrated that its reading was regarded as normative within the Syriac gospel tradition. More importantly, its connection to a Greek original cannot be established. The most that can be said is that a Syriac translator or corrector rendered the verse in a way similar to the NWT. It has not been established that this rendering is accurate. The evidence we have suggests that it was not. As Syriac Gospel scholar P.J. Williams writes:

"While the Greek may have been ambiguous, overwhelmingly ancient interpreters chose the opposite interpretation to that of the Watchtower" (P.J. Williams, PhD, private email to Robert Hommel, dated 1/6/2005.).

objection: Witness apologist Greg Stafford offers a number of arguments in favor of the NWT punctuation of Luke 23:43.

Codex Vaticanus

His first is that a major early manuscript of the New Testatment contains a punctuation mark - equivalent to a comma - after "today," just as does the NWT:

While punctuation in NT manuscripts of the first few centuries CE is not common, one of the best, if not the best witness to the text of the NT, Codex B or Vaticanus (Vatican 1209) of the fourth century CE, does have a mark of punctuation in Luke 23:43; the punctuation is not after �I say� but after the Greek word s�meron, �today" (Stafford, pp. 546-547).

Stafford says that a Vatican Library scholar verified by letter that the mark in question does not appear to be by a later copyist, due to the color of the ink. Mr. Stafford concludes that it dates from the 4th century and therefore offers textual support for the NWT punctuation from a reliable ancient Greek manuscript. Stafford, p. 547. Mr. Stafford does not quote the letter directly. He says simply that in response to "several questions regarding the punctuation of Luke 23:43," the Vatican scholar replied that the dot was "faded brown" and had not been traced over by the later copyist. Mr. Stafford does not name the author of the letter nor provide his qualifications as a textual critic, identifying him only as a "Patristics scholar." Importantly, it is Mr. Stafford's conclusion that the dot is an intentional punctuation mark dating from the 4th century, not the anonymous scholar's (at least, Mr. Stafford does not quote him as saying so).

Mr. Stafford is here responding to Dr. Julius Mantey, who in his famous letter to the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, writes the following:

Why the attempt to deliberately deceive people by mispunctuation by placing a comma after "today" in Luke 23:43 when in the Greek, Latin, German and all English translations except yours, even in the Greek in your KIT, the comma occurs after leg� (I say)..."

Mr. Stafford concludes: "Of course, while this [the comma in Codex B] does not prove anything regarding Luke's original text, it certainly disproves Mantey's claim that Greek manuscripts do not support the NWT's punctuation of Luke 23:43" (Stafford, p. 548). It is debatable whether Dr. Mantey was referring to ancient Greek manuscripts (he specifically writes "translations"); but in any event, Mr. Stafford's assertion (stated negatively) is that the dot in Codex B is an intentional punctuation mark, dating from the 4th Century, and that it supports the NWT.

Response: It is not at all clear that the dot in Codex B is an intentional mark of punctuation. It may nothing more than a dot or an accidental inkblot.

An 'accidental' inkblot or dot in Codex Vaticanus. The blot appears between the rho and kappa in sarkos ("flesh") in Romans 9:8.

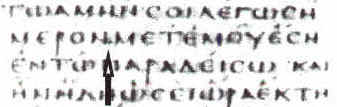

The Watchtower's published image of the alleged low-point punctuation in Luke 23:43, Codex Vaticanus.

If the dot is, indeed, an intentional mark of punctuation, it is almost certainly not by the original hand. "The point at the top of the line (�) (stigmh teleia, 'high point') was a full stop; that on the line (.) (upostigmh) was equal to our semicolon, while a middle point (stigmh mesh) was equivalent to our comma. But gradually changes came over these stops till the top point was equal to our colon, the bottom point became a full stop, and the middle point vanished, and about the ninth century A.D. the comma (,) took its place" (Robertson, Grammar, p. 242).The original scribe did not use the "low-point" dot, and when using punctuation (which he did rarely), he typically added an extra space, which is not the case here.

Typical spacing added after a mark of punctuation in Codex Vaticanus (between Luke 22:30 and 22:31)

Further, if the scribe intended to place a comma after s�meron, he would probably have used a middle-point as he did after sarka in Romans 9:5 (and various other places), not the low-point, which was more or less equivalent to our semi-colon. However, punctuation in early manuscripts, and particularly in Codex Vaticanus, was far from consistent. So, we must concede this it is possible that a scribe or corrector might use a low-point in a manner consistent with our modern comma; however, given the fact that the low-point does not appear to have been used at all by the 4th century scribe or his contemporary corrector, while they did (rarely) employ both the high-point and middle-point, it would seem most unlikely that one of them did so here. Robertson says: "B has the higher point as a period, and the lower point for a shorter pause" (Ibid.). However, Robertson does not say the "lower point" was by the original scribe or his 4th Century corrector.

Finally, to my knowledge, no commentators or textual critics have mentioned the alleged comma in Vaticanus. Bruce Metzger, in his Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, says nothing of it, even though he addresses the Curetonian Syraic (see above) in relation to the correct punctuation of Luke 23:43, and discusses the punctuation mark in Vaticanus at Romans 9:5. Metzger, p. 155 (c.f., pp. 459 - 462). As I was preparing this article, I corresponded briefly with Dr.Wieland Willker about the alleged comma in Vaticanus. Dr. Willker has a webpage dedicated to Codex Vaticanus and an online Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels. As a result of our correspondence, Dr. Willker added information about the dot in Vaticanus to the third edition of his Commentary. Dr. Willker agrees that the dot is "of unknown origin," and is not by the original scribe. He concludes:

The dot in B is not of much relevance because the punctuation question exists independent of it. The punctuation, if there was any at all, was, like spelling, irregular in the early MSS. Any punctuation in ancient MSS is VERY doubtful. The punctuation in Nestle-Aland or GNT is NEVER based on a punctuation in a MS. It is ALWAYS a decision based on grammar, syntax, linguistics, and exegesis (Willker, Textual Commentary, p. 436, emphasis in original).

Dr. Willker lists the following manuscripts which place hoti after leg�, thus emphasizing that "today" modifies "you will be with me...": L, 892, L1627, b, c, Co, and Sy-S. He lists AM 118 PS8, 11(1.8), Apo, and Hil as manuscripts that do the same thing with different syntax. He also lists several sources supporting a comma after "Today," but these all are from a posting on the B-Greek discussion list, each of which are examined later in this article.

The Vaticanus manuscript was originally written in the fourth century in brown ink, with a corrector soon thereafter making some slight changes. Then, a later scribe in the tenth or eleventh century traced over the lettering in black ink, skipping those letters or marks he thought to be incorrect, and making some additional changes ( Finegan, pp. 127-28.). As noted, Mr. Stafford (citing a letter from a Vatican Library scholar) says the dot is "faded brown" and concludes that it dates from the fourth century and not from the later medieval copyist. While the color may indicate an early date for the dot, this is not certain. Even if it is, it has not been established that it is from the original hand or the 4th century corrector, and the fact that it was not reinforced by the later corrector indicates that he regarded it as unintentional or in error. Dr. Peter M. Head, a specialist in NT manuscripts, writes:

I don't think it is punctuation. Certainly not in the original scribal production: there is nothing else like it on the whole opening (punctuation in Vaticanus is almost entirely only by spacing), it doesn't look like a dot, more like a blemish or as you said, a blot; and the spacing is all wrong for punctuation by the original scribe. I suppose it could be added later by someone wanting to repunctuate the text, but even so I'm not persuaded that the colour is the same as the other material introduced by the enhancer/accenter, so you have to attribute it to an unknown reader/punctuator. [Peter M. Head, PhD, personal email to Robert Hommel, dated 1/11/2005. Larry W. Hurtado, PhD, also suspects that the mark is a blot or blemish and not a mark of punctuation (personal email to Robert Hommel, dated 1/5/2005).]

Therefore, the most that can be said is that if the dot is intentional punctuation, it was not copied from an earlier exemplar by the original scribe, but was introduced - for an unknown reason - by an unknown hand at an uncertain time. This would seem thin evidence, indeed, of a textual tradition in the Greek manuscripts dating from the 4th century, as Mr. Stafford proposes.

But what if it could be established that the mark is intentional and dates from the 4th century (as unlikely as that seems) - does it then provide early support for the NWT punctuation? Yes and no. It would provide evidence apart from the Curetonian Syriac that someone long ago, due to the ambiguity of the Greek, understood (or misunderstood) the verse as the Watchtower does. But it would prove nothing with regard to what Luke intended. Mr. Stafford admits as much: "While this [a punctuation mark dating from the 4th century] does not prove anything regarding Luke's original text, it certainly disproves Mantey's claim that Greek manuscripts do not support the NWT's punctuation of Luke 23:43" (Stafford, p. 548, emphasis in original). Of course, this evidence only "certainly disproves Mantey" if a) Mantey meant "manuscripts" when he wrote "translations"; b) that the dot is an intentional punctuation mark and not an accidental blot; and c) that it actually dates from the 4th century. The textual scholars who punctuate our authoritative Greek New Testaments do not do so on the basis of punctuation in ancient manuscripts:

The presence of marks of punctuation in early manuscripts of the New Testament is so sporadic and haphazard that one cannot infer with confidence the construction given by the punctuator to the passage. (Metzger, p. 460, n. 2.)

Thus, even granting Mr. Stafford his argument, the presence of a punctuation mark (if such it is) in one early manuscript tells us nothing about how to properly punctuate Luke 23:43. The correct punctuation is a matter of exegesis, not of textual criticism.

Layton's translation of the Sahidic Coptic is not authoritative proof that the comma should follow "today." His interpretation represents a minority view and is not reflective of the broader consensus among Coptic scholars. Most translations of the Sahidic Coptic, such as those by Lambdin and Horner, place the comma before "today," aligning with traditional Christian doctrine. The Coptic text structure follows the same ambiguity as the Greek but is generally understood to support the traditional punctuation. Layton’s rendering is an interpretive decision, not a direct reflection of the grammatical rules.

The Curetonian Syriac is indeed one of two Old Syriac manuscripts. However, it does not outweigh the testimony of the Sinaitic Syriac, which predates it and agrees with the traditional punctuation. Syriac Peshitta, the standard and widely accepted Syriac text, supports the traditional reading. Even early Syriac commentators, like Ephrem the Syrian, interpret the verse as promising immediate entry into Paradise upon death. The Curetonian Syriac represents a minority textual tradition, and its divergence from the mainstream Syriac text diminishes its weight as evidence. According to Bruce M. Metzger, the majority of ancient Bible translations also follow the majority view, with only the Aramaic language Curetonian Gospels offering significant testimony to the minority view.

The hypostigme (low dot) in Vaticanus is not a reliable indication of punctuation. It could be an ink blot, a scribal error, or an idiosyncratic mark introduced by a later hand. Punctuation in early Greek manuscripts was inconsistent and rarely definitive. Notably, textual scholars like Metzger and Willker have dismissed the Vaticanus dot as irrelevant. Even if it were intentional, it reflects one scribe's interpretation, not a broader textual tradition. Vaticanus' alleged punctuation does not establish the NWT reading. Punctuation in ancient manuscripts does not carry the same interpretive authority as grammatical structure and broader textual evidence.

The phrase "Truly I say to you" (Ἀμὴν λέγω σοι) occurs nearly 70 times in the New Testament, and never is "today" connected with "I say to you." Instead, the content of the statement follows immediately.The JW interpretation would require the phrase to read something like "Truly I say today to you" (Ἀμὴν σήμερον λέγω σοι), but this is not the Greek structure. Greek syntax places "today" with the subsequent clause: "You will be with me in Paradise." The overwhelming grammatical evidence places "today" with "You will be with me in Paradise," making the NWT reading linguistically improbable.

While early Greek manuscripts did lack consistent punctuation, the context and parallels within Scripture support the traditional reading. The overwhelming consensus of ancient manuscripts (Greek, Latin, Syriac, and Coptic) aligns with the traditional interpretation. Translations like the Old Latin, Vulgate, and Peshitta universally render the verse as, "Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise." The consistency of traditional punctuation across ancient translations demonstrates a strong textual tradition contrary to the NWT rendering.

The immediate promise of Paradise aligns with Christ’s teaching about the soul's survival after death (e.g., Luke 16:19–31, Matthew 22:31–32). The thief’s body would die, but his soul would be in Paradise with Christ that day. Paul’s writings reinforce the belief in immediate fellowship with Christ upon death: “To be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8). This contradicts the Jehovah’s Witness teaching of "soul sleep." The traditional reading is consistent with biblical theology regarding the state of the soul after death, while the NWT rendering imposes doctrinal presuppositions on the text.

The NWT translation reflects the theological presupposition that the soul ceases to exist at death. This is not supported by the majority of ancient texts or Christian doctrine. Even in cases where translations differ slightly (e.g., Rotherham), the broader consensus among scholars, early Church Fathers, and textual traditions overwhelmingly supports the traditional reading. The NWT punctuation reflects theological bias rather than fidelity to the Greek text or historical interpretation.

Check THIS too.

-

113

Luke 23:43 the NWT

by Ade inluke 23:43 - and jesus said to him, "positively i say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.

nwt places comma here , giving a totally different meaning to the verse.

now the average jw uses this to back their doctrine and it seems in itself virtually impossible to reason with them on it.

-

aqwsed12345

Jehovah's Witnesses argue that the comma in Jesus’ statement, "Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise," should be placed after "today," rendering it: "Truly I say to you today, you will be with me in paradise." Their claim hinges on the lack of punctuation in ancient Greek manuscripts and a supposed Hebraic idiom emphasizing the timing of the statement rather than its fulfillment. The phrase "Amen I say to you" (Greek: Amēn legō soi) is a standard introductory formula used by Jesus over 70 times in the Gospels. In every instance, it introduces a solemn statement or promise and is never accompanied by a temporal adverb (today or otherwise) qualifying the act of speaking. Placing "today" with "I say to you" creates an unprecedented redundancy, as the audience would already understand that Jesus was speaking "today." By contrast, placing "today" with the subsequent promise emphasizes immediacy and aligns with the standard usage of this phrase throughout the Gospels. The natural reading of the Greek, Amēn soi legō, sēmeron met’ emou esē en tō paradeisō (Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise), connects "today" with the promise of being in paradise rather than with the act of speaking. This reading is consistent with nearly all translations, including Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox versions, reflecting the translators' understanding of the syntax and context.The New World Translation’s punctuation aligns with Jehovah’s Witness theology, which denies the immediate post-mortem existence of the soul. However, the interpretation of Luke 23:43 must stem from the text itself rather than theological presuppositions.

Jehovah's Witnesses assert that "paradise" refers to a future earthly state rather than an immediate post-mortem reward. Catholic teaching recognizes that before Christ's resurrection, the righteous dead resided in the limbus patrum (Abraham’s bosom) within Hades (Sheol). Christ's descent into Hades (1 Peter 3:19, Ephesians 4:9) liberated these souls, bringing them into heavenly paradise. Thus, Jesus’ promise to the thief can be understood as referring to this state of blessedness. The thief would join Jesus in Abraham’s bosom that very day, and after the Resurrection, the righteous would enter the full reality of heavenly paradise.

Jehovah's Witnesses argue that the promise could not have been fulfilled immediately because Jesus did not ascend to heaven until after His resurrection (John 20:17). This objection conflates Jesus’ bodily ascension with the immediate state of His soul after death. Catholic teaching affirms the hypostatic union—Jesus' divine and human natures remain united even in death. While His body lay in the tomb, His soul descended into Hades to proclaim victory and liberate the righteous. In this sense, Jesus was present in "paradise" (Abraham’s bosom) on the day of His death. Jesus' promise assures the thief of immediate entry into the blessed state of the righteous. This interpretation aligns with:

- Philippians 1:23: Paul expresses the desire to "depart and be with Christ," indicating immediate post-mortem communion with Jesus.

- 2 Corinthians 5:8: Paul states that to be "absent from the body" is to be "present with the Lord."

- Luke 16:22-23: The parable of Lazarus and the rich man portrays the dead as conscious and experiencing their respective rewards.

Addressing Specific Watchtower Objections

A. Coptic and Curetonian Syriac

While the Curetonian Syriac does place "today" with the phrase "Truly I tell you today," it is an isolated textual witness among ancient manuscripts. The Sinaitic Syriac, which predates the Curetonian, agrees with the majority reading: "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise." Furthermore, the Peshitta, the standard Syriac Bible, supports the traditional reading. The Sahidic and Bohairic Coptic translations also support the traditional placement of the comma before "today." Claims that the Coptic supports the Watchtower interpretation are unsubstantiated when compared to broader manuscript evidence. So a single variant reading like the Curetonian Syriac, especially when contradicted by older and more widely attested textual traditions, does not establish the legitimacy of the Watchtower’s translation. The overwhelming manuscript evidence—including Greek, Latin, Syriac, and Coptic—supports the traditional punctuation.

B. Matthew 12:40 and 1 Corinthians 15:3-4

Jehovah's Witnesses cite these passages to argue that Jesus remained "in the heart of the earth" (Hades) for three days, precluding His presence in paradise. This objection overlooks the distinction between Jesus’ soul and body. His soul was present in paradise (Abraham’s bosom) while His body lay in the tomb.

C. "Today" as a Hebraism

The claim that "today" serves as a Hebraic idiom emphasizing the time of speech lacks evidence in the Gospels. Luke consistently uses "today" to denote immediacy of fulfillment (e.g., Luke 2:11, 4:21, 19:9).

-

408

Is Jesus the Creator?

by Sea Breeze inthat's what the word says.

.

colossians 1:16. for by him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things have been created through him and for him..

-

aqwsed12345

Your argument against the authenticity of the phrase "our Lord and God Jesus Christ" in Polycarp's Letter to the Philippians—and by extension, your broader point about potential interpolations in early Christian writings—requires a detailed response. You correctly note that the Greek manuscript evidence for Polycarp's letter is incomplete and relies on late Latin manuscripts for the latter part. However, this does not automatically render the inclusion of "our Lord and God Jesus Christ" invalid. Several points need consideration. Many ancient works have come down to us in fragmentary or late manuscripts. For instance, much of classical literature is known from manuscripts no earlier than the Middle Ages. This does not negate the authenticity of those works; rather, it underscores the care required in textual criticism. While there are variations in the Latin manuscripts regarding "et deum" ("and God"), the presence of this phrase in four of the nine manuscripts is significant. Variations in wording are a common feature of manuscript traditions and must be weighed carefully, not dismissed outright. The phrase "our Lord and God Jesus Christ" aligns with the theological language of Polycarp's time. The early Christian community frequently referred to Jesus in terms that affirmed His divinity (e.g., John 20:28, Ignatius of Antioch).

You raise valid concerns about the possibility of interpolations in early Christian writings, citing Rufinus and examples from other Church Fathers. However, while Rufinus admits to "harmonizing" Origen's works with orthodox theology, this was not a systematic effort to alter all early Christian texts. The cases you cite (e.g., Clement, Dionysius of Alexandria) are specific examples, not evidence of widespread fabrication. Differences in manuscript traditions are normal, but they do not imply deliberate falsification. Textual criticism aims to identify the most likely original reading based on internal and external evidence. Polycarp was a disciple of the Apostle John and a contemporary of Ignatius of Antioch, whose writings unambiguously affirm Jesus' divinity (e.g., Ignatius’ letter to the Ephesians: "our God, Jesus Christ"). The phrase "our Lord and God Jesus Christ" fits the theological framework of Polycarp’s milieu, making interpolation less likely.

The expression "our Lord and God Jesus Christ" is consistent with early Christian theology. Thomas explicitly addresses Jesus as "My Lord and my God" (Ho Kyrios mou kai ho Theos mou). This confession of Jesus' divinity became a cornerstone of early Christian belief. Writing just decades before Polycarp, Ignatius repeatedly refers to Jesus as God (e.g., To the Romans 3:3: "our God, Jesus Christ"). The idea of Jesus' divinity was not a late development but an integral part of early Christian theology. As a disciple of the Apostle John, Polycarp's theology would naturally reflect Johannine Christology, which strongly emphasizes Jesus' divine nature (e.g., John 1:1, 10:30).

Michael Holmes' personal correspondence, where he suggests "et deum" may be a later addition, reflects the ongoing nature of textual criticism. However, textual criticism often involves differing opinions. Holmes' later reconsideration does not constitute definitive proof against the phrase's authenticity. Other scholars, such as J.B. Lightfoot, have defended the phrase. The broader context of Polycarp's writings emphasizes Christ's exalted status. Even if "et deum" were omitted, the remaining text still supports a high Christology consistent with early Christian belief.

Your broader assertion that no first-century Christian, including Paul, believed in a Trinity is not supported by the evidence. Paul refers to Jesus in divine terms (e.g., Philippians 2:6-11, Colossians 1:15-20, Titus 2:13). While Paul does not use the term "Trinity," his writings provide the foundation for later Trinitarian doctrine. The New Testament contains numerous references to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in ways that suggest a unified divine nature (e.g., Matthew 28:19, 2 Corinthians 13:14). The writings of Ignatius, Justin Martyr, and others demonstrate that belief in Jesus' divinity and the Triune nature of God was firmly established in the early church.

In the New Testament, Jesus Christ is referred to as κύριος (Lord) and θεός (God) in numerous instances, but according to Arians these do not mean anything special, it’s not a big deal, right? They argue that κύριος does not necessarily refer to Adonai, and thus ultimately to Yahweh, and that θεός may also have a more general meaning. But is this really what the apostles meant by using these terms?

In Ancient Greek, to convey "master" or "lord" in non-divine sense while avoiding the connotations of κύριος (kyrios), you could use:

- δεσπότης (despotes) - This term generally means "master" or "lord" in the sense of a ruler or one with authority over a household or dependents. While it can have hierarchical connotations, it is less tied to divinity in classical contexts.

- ἄναξ (anax) - This is a poetic or noble term often translated as "lord" or "master." It has heroic or noble associations, especially in Homeric contexts.

- ἄρχων (archon) - Meaning "ruler" or "chief," this term could be used for someone with authority in a civic or administrative role.

- ἡγεμών (hēgemṓn): Meaning "leader" or "governor," though it often denoted a political or military leader rather than a personal "lord" or "master."

The best choice depends on the context and the specific nuances you want to convey about the relationship or setting. δεσπότης is probably the closest neutral alternative in most general uses.

Question: if the apostles wanted to avoid Christ being understood as a divine Lord in the proper sense, and wanted to avoid the YHWH-Adonai association, why didn't they use one of these terms instead of κύριος?

But likewise, the apostles repeatedly call Christ θεός, and instead, numerous expressions would have been available if they wanted to express that he was partly divine, godlike, kind of god:

- θεῖος (theios): "Divine," "godlike," or "of the gods." Often used adjectivally to describe something extraordinary, inspired, or blessed by the gods, such as divine wisdom (θεῖα σοφία). It does not imply the being is a full deity. This term works well for attributing divine qualities without implying the individual is a full god.

- ἡμίθεος (hemitheos): "Demigod," literally "half-god. Used for mythological figures, typically heroes or mortals with divine parentage or divine favor. For example, Heracles is referred to as a ἡμίθεος. This explicitly signals a partial divinity or divine favor, emphasizing a lower status than a full deity.

- ἥρως (hērōs): "Hero," a mortal of exceptional ability, often regarded as semi-divine. Heroes like Achilles or Odysseus were sometimes venerated and associated with divine qualities. While primarily mortal, ἥρως carries connotations of extraordinary, divine-like qualities.

- θεϊκός / θεϊνός (theïkos / theinos): "Godlike," "pertaining to a god." These adjectival forms emphasize qualities that resemble those of a deity but do not imply full divinity. For example, extraordinary beauty or wisdom could be described as θεϊκή. Flexible for metaphorical or partial divine associations.

- θεώτερος (theōteros): "More divine." Comparative form, used to imply that someone or something is more divine or godlike than others, but not absolutely divine. It highlights relative, rather than absolute, divinity.

- δαίμων (daimōn): Originally referred to a spirit or lesser deity, often a personal or local divine force. Associated with a range of supernatural beings, not inherently good or evil. In later usage, particularly in Christian contexts, it took on a negative connotation (as "demon"), but in classical texts, it was more neutral. Suitable for referring to a lower-order divine being or a guiding force without implying supreme authority.

Question: if the apostles really wanted to avoid understanding Christ as God in the absolute, monadic sense, then why didn't they use one of the terms instead of θεός?

-

92

Ecclesiastes 9:5 -"the dead know nothing at all"

by aqwsed12345 inthe narrator of the book of ecclesiastes had very little knowledge of many things that jesus and his apostles later preached.

the author does not make statements, but only wonders (thinks, observes, often raises questions, and leaves them open).

he looked at the world based on the law of moses and found nothing but vanity, as the earthly reward promised in the law did not always accompany good deeds and earthly punishment for evil deeds.

-

aqwsed12345

The Jehovah's Witnesses' interpretation of Luke 23:43 is one of the most contested translations in their New World Translation (NWT). Their punctuation places the comma after "today" rather than before it, rendering the verse as:

"Truly I tell you today, You will be with me in Paradise."

This interpretation attempts to align the text with their theology, which denies the immediate existence of the soul after death and the possibility of entering Paradise on the day of death. However, this interpretation introduces several theological, linguistic, and exegetical problems

1. Punctuation in Ancient Greek

The Watchtower rightly notes that ancient Greek manuscripts lacked punctuation. However, this does not grant liberty for arbitrary punctuation. Translators must determine punctuation based on context, grammar, and the consistent patterns of speech in Scripture. The overwhelming majority of translations, both ancient and modern, place the comma before "today" for several reasons:

a) The "Amen I tell you" Formula

The phrase "Amen I tell you" (Greek: ἀμήν σοι λέγω) is used 74 times in the Gospels and never includes an adverb like "today" to modify the formula. It always introduces the main statement that follows. Placing "today" with "Amen I tell you" would constitute an unprecedented and irregular usage in Jesus' speech.

For instance:

- In Luke 5:24, Jesus says, “But that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins”. The phrase is immediately followed by the subject of His declaration.

- Similarly, in Luke 18:17, Jesus says, "Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it.”

The uniformity of this formula strongly indicates that in Luke 23:43, the correct rendering is, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

2. What Did Jesus Mean by "Today"?

The Watchtower argues that Jesus’ use of "today" simply emphasizes the moment of His speaking, rather than the timing of the promise's fulfillment. However, this is redundant and unnecessary.

- Contextual Redundancy: If Jesus merely meant, "I tell you today," this would be superfluous. Of course, He is speaking "today"—when else would He be speaking? As the Catholic apologist John Gill rightly points out, this interpretation lacks sense or purpose.

- Theological Coherence: Jesus' words contrast with the thief’s request. The thief asked, “Remember me when you come into your kingdom”—a future event. Jesus assures him, “Today you will be with me in Paradise”—shifting the focus to immediate consolation and hope.

3. The Meaning of "Paradise"

Jehovah's Witnesses claim that "Paradise" in this verse refers to a future earthly paradise (an Edenic restoration). However, this interpretation is inconsistent with the New Testament use of the term:

a) Paradise as Heaven

- In 2 Corinthians 12:3-4, St. Paul describes being caught up into "Paradise" and identifies it as the third heaven—a clear reference to the divine presence.

- In Revelation 2:7, "Paradise" is associated with the tree of life, which is in the heavenly realm of God.

Thus, "Paradise" in Luke 23:43 most naturally refers to heaven, the state of blessedness in God's presence, not an earthly restoration.

b) "With Me in Paradise"

Jehovah's Witnesses interpret "with me" to mean that the thief would eventually share an earthly paradise. However, this interpretation undermines Jesus' own words. If "Paradise" is an earthly location, then Jesus Himself would also be in that location. Yet Scripture affirms that Christ ascended to heaven (Acts 1:9-11). The thief’s promised destination is where Christ is—in the immediate presence of God.

4. Immediate Afterlife

The Catholic Church teaches that souls experience immediate judgment after death, entering either heaven (directly or via purgatory), hell, or (in the case of the righteous who died before Christ) the Limbus Patrum. This teaching is supported by:

- Philippians 1:23: St. Paul expresses a desire to “depart and be with Christ.”

- Revelation 6:9-10: The souls of martyrs are depicted as conscious and present in heaven, awaiting the resurrection.

- Luke 16:22: The parable of Lazarus and the rich man shows Lazarus immediately in Abraham's bosom, a place of rest and communion with the righteous.

Jehovah's Witness theology, which denies the soul's immediate existence after death, contradicts these passages and relies on selective reinterpretation to fit their doctrinal framework.

5. Theological Problems in the Watchtower's Interpretation

a) An Inconsistent Translation

The Watchtower’s placement of the comma after "today" in Luke 23:43 is inconsistent with their own treatment of similar verses. For example, in the 73 other occurrences of "Amen I tell you," they place the punctuation before the emphasized statement, not after.

b) Christ’s Presence in Paradise

If the thief is promised to be “with me in Paradise,” and Paradise is an earthly location, then Jehovah's Witnesses would need to explain why Christ Himself is depicted as being there. Their theology typically restricts Christ to heavenly rulership, making this interpretation incoherent.

c) The Timing of the Promise

While Jehovah's Witnesses argue that Christ could not have been in Paradise on that day because He was dead and in the grave, Catholic theology resolves this through the doctrine of the Harrowing of Hell. Christ’s soul, fully united to His divine nature, descended into Hades to proclaim victory to the righteous (1 Peter 3:18-19). Thus, Christ's presence in "Paradise" on that day is entirely consistent with His dual natures and His redemptive mission.

Conclusion

The Watchtower's interpretation of Luke 23:43 is not based on sound exegesis but on theological presuppositions designed to support their denial of the soul's immediate afterlife and Christ's divinity. In contrast, the Catholic understanding, rooted in the context of Scripture, Tradition, and linguistic evidence, affirms:

- The thief was assured of immediate fellowship with Christ upon death.

- "Paradise" refers to the heavenly state, not an earthly restoration.

- The phrase "Amen I tell you today" is consistent with Christ's formulaic declarations, emphasizing the immediacy and certainty of His promise.

This verse offers profound comfort and hope, demonstrating Christ's boundless mercy and the immediate joy awaiting those who place their trust in Him. For the thief, and for all who die in Christ's grace, Paradise is not a distant hope but an immediate reality.

-

113

Luke 23:43 the NWT

by Ade inluke 23:43 - and jesus said to him, "positively i say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.

nwt places comma here , giving a totally different meaning to the verse.

now the average jw uses this to back their doctrine and it seems in itself virtually impossible to reason with them on it.

-

aqwsed12345

The Watchtower Society’s interpretation of Luke 23:43 claims that Jesus’ promise to the penitent thief—“You will be with me in paradise”—refers not to an immediate entrance into heavenly paradise but to a future, earthly paradise after the resurrection. Their New World Translation (NWT) renders the verse: “Truly I tell you today, You will be with me in Paradise,” placing the comma after "today."

1. The Punctuation Argument

A) No Punctuation in Greek Manuscripts

The Watchtower rightly notes that the original Greek manuscripts lack punctuation. However, punctuation in translation should follow the context and standard usage patterns in the Greek New Testament. The phrase “Amen I say to you…” (Greek: Amēn soi legō...) occurs over 70 times in the Gospels. In every instance, Jesus emphasizes the promise or teaching that follows, without any adverb of time like "today" qualifying the introductory phrase.

Placing "today" (sēmeron) with “I say to you” creates an unnecessary redundancy. Jesus did not need to specify when He was speaking; it is self-evident that He was speaking “today” (as opposed to yesterday or tomorrow). The correct reading, adopted by nearly all translations, places the comma before "today," making the promise immediate: “Today, you will be with me in paradise.”

B) The Formula “Amen I say to you”

The construction “Amen I say to you” (Amēn legō humin) is a distinctive formula used by Jesus to introduce solemn declarations. Nowhere in the Gospels does this phrase include an adverb like "today." If Luke 23:43 were the sole exception, the burden of proof lies with the Watchtower to demonstrate why this verse deviates from Jesus’ established pattern. The evidence strongly suggests that "today" belongs with the subsequent promise, emphasizing its immediacy.

2. The Meaning of “Paradise”

A) Heaven, Not Earth

The term "paradise" (paradeisos) is used three times in the New Testament (Luke 23:43, 2 Corinthians 12:4, Revelation 2:7), and it consistently refers to the heavenly realm where God’s presence dwells. In 2 Corinthians 12:4, Paul describes being caught up into “paradise,” a place synonymous with the "third heaven." Revelation 2:7 portrays paradise as the dwelling of the Tree of Life, located in the presence of God. There is no indication that "paradise" refers to a future earthly restoration.

The Watchtower’s interpretation reduces "paradise" to an earthly kingdom, contradicting the context of these other passages. Moreover, Jesus tells the thief, “You will be with me in paradise.” If paradise were only an earthly state, this would imply that Jesus Himself would reside in this earthly paradise, which contradicts the Watchtower’s teaching that Jesus reigns in heaven.

B) The Catholic Understanding

Catholic theology identifies "paradise" as the blessed state of communion with God, often equated with heaven. When Jesus promises the thief, “Today you will be with me in paradise,” He refers to the immediate post-mortem state where the righteous are united with God. This aligns with other biblical passages describing the immediate reward for the faithful upon death (e.g., Philippians 1:23, 2 Corinthians 5:8).

3. Theological Implications

A) Immediate Reward After Death

Catholic doctrine teaches that the righteous enter a conscious state of joy immediately after death. Jesus’ promise to the thief affirms this. The Watchtower denies the immediate post-mortem existence of the soul, claiming that the dead are unconscious until the resurrection. However, this is contradicted by passages such as:

- Philippians 1:23: Paul desires “to depart and be with Christ,” implying immediate union with Jesus after death.

- Revelation 6:9-11: The souls of martyrs are depicted as conscious and crying out to God.

- Luke 16:22-23: The parable of Lazarus and the rich man portrays the dead as fully conscious.

B) The Limbus Patrum

Catholic tradition acknowledges the Limbus Patrum (Limbo of the Fathers), where the righteous who died before Christ’s resurrection awaited redemption. The promise of "paradise" to the thief need not conflict with this belief, as Christ, in His divine nature, could simultaneously be present in paradise and in the realm of the dead. This harmonizes with passages describing Christ’s descent into Hades (e.g., 1 Peter 3:18-20) to preach to the spirits in prison.

4. Addressing Watchtower Objections

A) “Today” as a Hebraism

The Watchtower argues that "today" functions as a Hebrew idiom emphasizing the time of speech (e.g., Deuteronomy 4:26). However, such idioms are irrelevant here because:

- Jesus’ phraseology “Amen I say to you” is unique to Him and not modeled after Hebrew idioms.

- In the New Testament, "today" consistently emphasizes the immediacy of fulfillment (e.g., Luke 19:9, “Today salvation has come to this house”).

B) Jesus Did Not Ascend to Heaven That Day

The Watchtower points to John 20:17, where Jesus tells Mary Magdalene, “I have not yet ascended to the Father,” as evidence that Jesus did not go to paradise on the day of His crucifixion. However, this misunderstands the distinction between Jesus’ bodily ascension (40 days after His resurrection) and the state of His soul after death. Jesus’ soul, united with His divine nature, entered paradise upon death, as evidenced by His promise to the thief.

5. Other Linguistic and Contextual Considerations

A) Consistency Across Translations

Virtually all Bible translations—Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox—place the comma before "today," indicating that Jesus promised the thief immediate entrance into paradise. The NWT’s unique punctuation reflects theological bias rather than linguistic accuracy.

B) Jesus’ Emphasis

The thief’s request was for a future remembrance in Christ’s kingdom. Jesus’ response surpasses this request, offering not a delayed reward but immediate communion: “Today you will be with me in paradise.” This contrasts with the Watchtower’s view, which diminishes the immediacy and intimacy of Jesus’ promise.

Conclusion

The Watchtower’s interpretation of Luke 23:43 stems from a theological presupposition that denies the immediate post-mortem existence of the soul and distorts the biblical concept of paradise. By examining the linguistic, contextual, and theological evidence, it becomes clear that Jesus’ promise to the thief affirms the immediate reward of the faithful after death. The traditional punctuation—“Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise”—reflects the plain meaning of the text, consistent with Jesus’ teaching and the hope of eternal life in communion with God.

-

73

"Jehovah" In The New Testament.

by LostintheFog1999 ini see they have updated their list of translations or versions where some form of yhwh or jhvh appears in the new testament.. https://www.jw.org/en/library/bible/study-bible/appendix-c/divine-name-new-testament-2/.

-

aqwsed12345

Refuting the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Claim that the Apostolic Authors Originally Included the Tetragrammaton in the New Testament

The Jehovah’s Witnesses argue that the original New Testament autographs contained the Tetragrammaton (YHWH) in some form—whether in Hebrew, Paleo-Hebrew script, or transliterated as ΙΑΩ. However, this claim is not supported by historical, textual, or theological evidence. Below, I will demonstrate why this hypothesis is untenable, focusing on the lack of indirect evidence, the absence of reports of such manuscripts in early Christian sources, the historical context of early Christianity, and the absence of any controversy over the alleged removal of the Tetragrammaton.

1. Indirect Evidence Should Exist—But Does Not

When scholars discovered Greek Old Testament manuscripts in the 20th century that contained the Tetragrammaton, such as P. Fouad 266 or 4Q120, this was not a shocking revelation. Early Christian writers like Origen and Jerome had already described the existence of Septuagint manuscripts with the Tetragrammaton written in Hebrew or Paleo-Hebrew characters. This indirect evidence provided historical context for the eventual discovery of these manuscripts.

However, if the New Testament originally included the Tetragrammaton, we should expect similar indirect evidence in early Christian writings. Yet no early Christian source, including those who had access to the earliest New Testament manuscripts, ever mentions the presence of the Tetragrammaton in the New Testament. The silence of these sources is deafening, especially when compared to their acknowledgment of the Tetragrammaton in Old Testament manuscripts.

Theological Library of Caesarea Maritima:

- The Theological Library of Caesarea Maritima, founded by Pamphilus and expanded by Origen, was the largest Christian library of antiquity. Scholars such as Gregory Nazianzus, Basil the Great, and Jerome studied there.

- If any manuscripts of the New Testament containing the Tetragrammaton existed, they would have been preserved in this library. Yet none of these scholars ever mentions a Tetragrammaton in the New Testament, even though Jerome specifically documented textual variants when producing the Vulgate.

This lack of evidence strongly suggests that the Tetragrammaton was never part of the New Testament text.

2. Absence of the Tetragrammaton as an Issue in Early Christianity

The early Christian period was marked by numerous theological disputes, with different factions accusing one another of heresy and Scripture manipulation. If the proto-orthodox Christians had removed the Tetragrammaton from the New Testament, we would expect their theological opponents to use this as ammunition against them. Yet there is no record of any group accusing the proto-orthodox of such a tampering.

Key Historical Context:

- Polycarp of Smyrna and other proto-orthodox figures faced accusations of heresy from theological opponents like the Gnostics or Marcionites. However, no group ever accused them of removing the Tetragrammaton from the New Testament.

- The absence of the Tetragrammaton was not a point of contention, even during highly charged debates over Christology, Scripture, and ecclesial authority.

This historical silence suggests that the Tetragrammaton was never part of the New Testament to begin with. If it had been, its removal would surely have been a significant theological issue.

3. Who Could Have Made Such a Decision?

The Jehovah’s Witnesses claim implies that someone had the authority and ability to systematically remove the Tetragrammaton from all New Testament manuscripts. However, this is historically implausible.

Comparison with the Qur'an and Uthman:

- When Caliph Uthman standardized the Qur'an in the 7th century, dissenting textual traditions still survived, and variant readings are documented in Islamic history.

- By contrast, no evidence exists of dissenting textual traditions in Christianity where the Tetragrammaton was retained in the New Testament. The process of replacing the Tetragrammaton would have required unprecedented coordination across the diverse and dispersed Christian communities of the Roman Empire, something no single authority in early Christianity could achieve.

No Centralized Authority in Early Christianity:

- The papacy as an institution was not yet fully developed in the 1st and 2nd centuries. Christianity was highly decentralized, with regional leaders such as bishops overseeing local churches. There was no mechanism for universally enforcing such a change.

- The proto-orthodox Christians lacked the power to standardize all New Testament manuscripts, especially when many were in circulation and held by diverse groups, including theological opponents.

The lack of both evidence and a plausible historical mechanism for such a widespread alteration further undermines the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ claim.

4. No External Evidence of the Tetragrammaton in Christian Worship

If early Christians regularly invoked the Tetragrammaton in their worship, we would expect external sources to comment on this. Yet external writers, such as Roman officials or pagan observers, consistently describe Christian worship as centered on Jesus as Lord (κύριος), not on YHWH or ΙΑΩ.

Pliny the Younger:

- In his letter to Emperor Trajan (c. 112 CE), Pliny describes Christian worship as follows:

- "They were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god..."

- Pliny does not mention Christians invoking the Tetragrammaton, even though such a practice would have caused great scandal to Jews.

Alexamenos Graffito:

- The Alexamenos graffito (c. 2nd century) depicts a Christian figure worshiping a crucified donkey, with the inscription:

- "Alexamenos worships [his] God" (Ἀλεξάμενος σέβεται θεόν).

- This graffiti mocks Christian worship but makes no mention of the Tetragrammaton. The absence of any reference to YHWH or ΙΑΩ suggests that the Tetragrammaton was not part of early Christian practice.

The consistent testimony of external sources aligns with the internal evidence of Christian manuscripts: early Christians invoked Christ as Lord and did not use the Tetragrammaton in their worship.

5. Conclusion

The Jehovah’s Witnesses’ claim that the Tetragrammaton was originally included in the New Testament autographs is untenable for several reasons:

- Indirect Evidence Is Absent: Unlike the case of the Septuagint, where early Christian writers like Origen and Jerome noted the presence of the Tetragrammaton, no similar reports exist for the New Testament.

- Theological Silence: The absence of the Tetragrammaton was never an issue in early Christian theological disputes, despite the fierce accusations of heresy that characterized the period.

- Impossibility of Systematic Removal: The decentralized nature of early Christianity and the lack of any central authority make it implausible that the Tetragrammaton could have been systematically removed from all manuscripts.

- No External Evidence: Roman and pagan sources describe Christian worship as focused on Jesus as Lord (κύριος), with no mention of the Tetragrammaton.

In light of these points, the claim that the Tetragrammaton was originally part of the New Testament does not hold up to historical, textual, or theological scrutiny. Early Christian usage of κύριος reflects continuity with Jewish tradition, not a conspiracy to obscure the divine name.

-

51

Theocratic Warfare and Taqiyya

by aqwsed12345 inthe concept of strategic deception exists in several religious and ideological contexts.

in this article, we will explore and compare the theocratic warfare doctrine of the watchtower society and taqiyya in islam.

both concepts have parallels in their mechanisms of permitting deception for religious purposes but differ significantly in their application and historical roots.. 1. theocratic warfare: the "rahab method".

-

aqwsed12345

A Comparative Critique: The Divisive Taxonomies of Jehovah’s Witnesses and Islam's Dar Framework

The division of humanity into categories has historically been a tool for delineating insiders from outsiders, reinforcing group identity, and managing perceived threats. In this article, we critically analyze the categorization systems employed by Jehovah’s Witnesses (JWs) and classical Islamic jurisprudence, focusing on how these frameworks serve as a "friend-enemy recognition system" to shield their core ideologies from critique.

Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Taxonomy of Humanity

Jehovah’s Witnesses employ an intricate system to categorize individuals into three primary groups, each serving a specific purpose in their theological framework:

- Those who have never been Jehovah’s Witnesses:

- 1A) Opposers: These are knowledgeable non-Witnesses who actively speak against the sect. Their critiques are dismissed as biased, emotionally driven, or ill-informed.

- 1B) Neutral or Uninformed: This group represents a blank slate (tabula rasa), individuals unfamiliar with JW doctrines. Their criticisms are easily dismissed with, "You don't understand because you’ve never been one of us."

- Active Jehovah’s Witnesses (Group 2): These are the insiders who adhere to JW teachings. They are shielded from external critiques and dissuaded from voicing internal dissent to avoid expulsion into the next category.

- Former Jehovah’s Witnesses:

- 3A) Disfellowshipped ("Removed"): Individuals formally expelled from the congregation for perceived misconduct or dissent.

- 3B) Voluntarily Disassociated: Those who separate themselves without formal disciplinary action.

Both subcategories of Group 3 are labeled "apostates," and interaction with them is strictly forbidden. JW literature often employs pejorative language, describing such individuals as "mentally diseased."

This insider jargon ensures every critique is delegitimized. Group 1A’s arguments are dismissed as biased; Group 1B’s as uninformed; Group 2 are conditioned not to critique, and Group 3 are shunned as inherently unreliable. This structure isolates members and reinforces the group’s narrative of exclusivity and infallibility.

The Islamic Dar Framework

Classical Islamic jurisprudence also divides the world into categories, albeit with territorial rather than individual focus. The framework historically aimed to guide the expansion of Islamic rule:

- Dar al-Islam ("House of Islam"): Territories under Islamic governance where Sharia law prevails. This corresponds to JW Group 2—those inside the fold who abide by the rules and cannot critique the system without risking expulsion.

- Dar al-Sulh or Dar al-Ahd ("House of Treaty/Truce"): Regions at peace with Muslim states but not under Islamic rule. These areas, like JW Group 1B, are seen as neutral zones, potential allies, or fields for proselytization.

- Dar al-Harb ("House of War"): Territories in conflict with Islamic states or those perceived as threats to Islam. Analogous to JW Groups 1A, 3A, and 3B, these are the ideological or physical "enemies" whose resistance must be subdued or ignored.

The dar classifications primarily served legal and military purposes, determining whether Muslims should engage in jihad, establish treaties, or focus on dawah (peaceful proselytization). Classical Islamic scholars debated these definitions, with many modern jurists considering them obsolete in a globalized world of nation-states.

The Role of These Frameworks: Shielding from Critique

Both systems serve to deflect criticism and reinforce internal cohesion. For JWs, the taxonomy categorizes all potential critics into delegitimized groups:

- Group 1A (Opposers): Criticisms are dismissed as emotional or dishonest.

- Group 1B (Neutral): Critiques are invalidated due to lack of insider knowledge.

- Groups 3A and 3B (Former Members): These individuals are dehumanized and shunned.

In Islam, the dar framework was originally used to delineate areas of governance and influence, but its effects are similar in some interpretations:

- Dar al-Harb: Resistance or critique from these areas is framed as illegitimate due to their opposition to Islamic rule.

- Dar al-Islam: Internal dissent is suppressed to maintain religious harmony and unity under Islamic governance.

- Dar al-Sulh: Neutral zones are seen as potential converts or allies, and their critiques are often downplayed.

A "Friend-Enemy Recognition System"

These frameworks operate as "friend-enemy recognition systems," a term borrowed from political theory to describe how groups establish boundaries and manage perceived threats. This approach simplifies complex human dynamics into binary categories, fostering an "us versus them" mentality. Critique, whether internal or external, is neutralized as follows:

- It is dismissed outright (1A/Group 3).

- It is invalidated due to lack of insider experience (1B/Dar al-Sulh).

- It is prevented altogether through social or doctrinal pressure (2/Dar al-Islam).

The Ethical and Theological Implications

Both systems share a key flaw: they prioritize group identity over intellectual and theological honesty. By preemptively categorizing and dismissing critics, they avoid engagement with uncomfortable questions or dissenting perspectives.

For JWs, this fosters isolationism, stifles intellectual freedom, and perpetuates harmful practices like shunning. In Islam, while the dar framework was initially a geopolitical tool, some modern interpretations risk creating similar exclusionary dynamics, alienating critics and perpetuating sectarian divides.

Conclusion

The taxonomy of humanity employed by Jehovah’s Witnesses and the classical Islamic dar framework both serve as mechanisms to delineate insiders from outsiders. While their contexts and applications differ, their shared function as tools for critique deflection and group cohesion reveals a common thread of exclusivism. For both, moving beyond these binary frameworks could foster a more open and dialogic approach to faith, allowing for constructive criticism and mutual understanding in a pluralistic world.

-

51

Theocratic Warfare and Taqiyya

by aqwsed12345 inthe concept of strategic deception exists in several religious and ideological contexts.

in this article, we will explore and compare the theocratic warfare doctrine of the watchtower society and taqiyya in islam.

both concepts have parallels in their mechanisms of permitting deception for religious purposes but differ significantly in their application and historical roots.. 1. theocratic warfare: the "rahab method".

-

aqwsed12345

@slimboyfat

The claim relies on Hurtado’s statement that κύριος in the LXX “seems to have developed sometime in the second century or so.” However, this does not mean Hurtado argued that κύριος was absent from all LXX manuscripts before the second century CE or that its introduction was a Christian innovation. Instead, Hurtado’s broader context clarifies that the substitution of YHWH with κύριος reflects Jewish scribal practices, not Christian alterations. Hurtado acknowledges that early Greek manuscripts of the Old Testament show a variety of treatments of the Tetragrammaton, including transliterations like ΙΑΩ and the Paleo-Hebrew script for YHWH. However, he does not claim this variety excludes the use of κύριος. Instead, Hurtado argues that the transition to using κύριος was part of Jewish scribal traditions over time. Hurtado’s assertion that κύριος became the dominant rendering of YHWH by the second century CE reflects the state of the majority of surviving manuscripts, not evidence of Christian interference. He does not argue that κύριος was a Christian innovation but rather that it reflects a Jewish scribal decision in continuity with the oral substitution of Adonai for YHWH. Hurtado explicitly states in other works, such as The Earliest Christian Artifacts, that κύριος was widely used in pre-Christian Jewish texts and was inherited by Christians. The substitution of YHWH with κύριος aligns with Jewish reverence for the divine name and their tradition of not vocalizing it.

The argument also misrepresents Hurtado’s discussion of Paul’s use of the LXX. Hurtado suggests that Paul may have had access to manuscripts retaining the Tetragrammaton (e.g., in Hebrew script), but this is not a universal claim about all LXX manuscripts in the first century CE. Hurtado’s point is that Paul’s deliberate application of YHWH texts to Jesus reflects an exegetical move grounded in the recognition of Jesus’ divine identity, not confusion caused by ambiguous textual renderings. Paul’s use of LXX passages referring to YHWH (e.g., Joel 2:32 in Romans 10:13) reflects a deliberate theological decision to identify Jesus with YHWH, regardless of whether the manuscripts Paul used contained YHWH or κύριος. The presence of YHWH in some early LXX manuscripts does not undermine the fact that κύριος was also widely used in Jewish and Christian contexts. The claim fails to account for the diversity in LXX textual traditions, where κύριος coexisted with other renderings of the divine name. Hurtado does not argue that the use of κύριος was exclusively a second-century development but rather highlights its dominance in the extant manuscript tradition by that time.

The evidence overwhelmingly shows that κύριος was a Jewish innovation, not a Christian one. Early Jewish scribes translated YHWH as κύριος in the LXX to align with the oral substitution of Adonai. This practice predates Christianity, and there is no evidence of a deliberate Christian effort to introduce κύριος into the text. The Septuagint was translated by Jewish scholars in the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE, and κύριος appears as the rendering of YHWH in the majority of extant LXX manuscripts. Variants like ΙΑΩ or Paleo-Hebrew YHWH reflect localized or sectarian traditions, not the normative Jewish practice. As Emanuel Tov notes, these variations were likely reintroductions of the Tetragrammaton in specific contexts, not the original translational approach.

The substitution of YHWH with Adonai in Jewish liturgical readings naturally led to the use of κύριος in Greek translations. This aligns with the Jewish reverence for the divine name and does not reflect a later Christian conspiracy. Early Christian scribes developed the nomina sacra (e.g., ΚΣ for κύριος) to mark sacred names, continuing the Jewish tradition of reverencing the divine name. This practice reinforces the continuity between Jewish and Christian treatments of sacred texts.

The claim that κύριος was introduced by Christians in the second century CE ignores the broader historical and textual evidence of its Jewish origins and early use in the LXX. The use of κύριος predates the second century CE, as demonstrated by extant manuscripts like the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus, which preserve this rendering consistently. These manuscripts reflect a tradition inherited from Jewish translators of the LXX. The New Testament authors, most of whom were Jewish, adopted the LXX as their authoritative Scripture. Their consistent use of κύριος reflects continuity with Jewish textual practices, not a theological innovation or conspiracy. If κύριος were a second-century Christian invention, we would expect to find transitional manuscripts or objections from Jewish or early Christian communities. However, no such evidence exists. The uniformity of κύριος in Christian manuscripts reflects its widespread acceptance within the Jewish tradition, not a deliberate replacement.

-

51

Theocratic Warfare and Taqiyya

by aqwsed12345 inthe concept of strategic deception exists in several religious and ideological contexts.

in this article, we will explore and compare the theocratic warfare doctrine of the watchtower society and taqiyya in islam.

both concepts have parallels in their mechanisms of permitting deception for religious purposes but differ significantly in their application and historical roots.. 1. theocratic warfare: the "rahab method".

-

aqwsed12345

@slimboyfat

The statement that "Hurtado doesn’t specify Christian or Jewish" is misleading because Hurtado’s writings consistently focus on Jewish liturgical and scribal practices regarding the use of Kyrios. While Hurtado acknowledges the second-century development of the scribal standardization of writing Kyrios in LXX manuscripts, he ties this development to Jewish practices rather than Christian innovations. Hurtado notes that the oral substitution of Kyrios for the Tetragrammaton was already a well-established Jewish custom prior to the second century CE. The second-century development he refers to concerns the growing standardization of this practice in written manuscripts, not its introduction by Christians. This distinction is critical and directly contradicts any alignment with Kahle's view that Christians introduced Kyrios into the LXX. The claim that Hurtado’s position is “at odds” with Pietersma, Rösel, and others who argue for Kyrios as the original rendering is also inaccurate. Hurtado’s acknowledgment of a second-century scribal standardization does not negate the possibility that Kyrios was already a rendering for YHWH in some early LXX manuscripts, as Pietersma and Rösel argue. Hurtado’s focus on standardization simply reflects the evidence of increased consistency in written texts during this later period.

While early manuscripts like Papyrus Fouad 266 preserve the Tetragrammaton, it is incorrect to suggest that Kyrios was entirely absent prior to the second century CE. There is evidence of diversity in how YHWH was rendered, including transliterations like ΙΑΩ and the use of Kyrios. Hurtado’s argument acknowledges this diversity while noting that Kyrios became dominant in later manuscripts, reflecting broader liturgical and theological trends. Pietersma and Rösel’s arguments that Kyrios may have been an original rendering for YHWH in some LXX texts are not incompatible with Hurtado’s observations about later scribal practices. The standardization of Kyrios in the second century CE represents a shift in scribal conventions, not the invention of Kyrios as a rendering for YHWH. But even if Pietersma's view is wrong, there are still several unproven claims:

- Let's assume that the cited Greek OT manuscript fragments "prove" that the Septuagint was translated this way by the Seventy, including the Tetragrammaton.

- This does NOT prove that this was the LXX version that the apostles used, accepted, and proclaimed the Tetragrammaton in their preaching

- Even if the apostles used such an version, it does not prove that the Tetragrammaton was inserted into the NT and later "erased" by someone for some heretical bias.

So this is anything but a "smoking gun", but completely wishful thinking, speculation. This is like the prosecutor in a criminal trial arguing that "since the kitchen knife was not in the drawer, this proves beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant was the one who committed the murder."

You cannot give a satisfactory answer to the question: Who made the decision to replace YHWH (or ΙΑΩ) with κύριος? Even more specifically: Who was the “Caliph Uthman” of the “apostate” (=proto-orthodox) Christianity who ordered the standardization of the NT and, under this heading, the tampering with the text?

While it is true that New Testament writers were primarily Jewish and familiar with the Tetragrammaton, the evidence does not support the idea that they used it in their writings. The consistent use of Kyrios in all surviving manuscripts suggests that the authors followed the established Greek tradition of substituting Kyrios for YHWH. The presence of the Tetragrammaton in some LXX manuscripts does not prove that the NT authors included it in their writings. By the first century CE, Kyrios was already well-established in oral and written traditions, making it the most likely term used by NT writers when quoting the LXX. The argument that the divine name might have been included to emphasize continuity with the Hebrew Scriptures is speculative and unsupported by manuscript evidence. The NT writers consistently used Kyrios to apply Old Testament passages about YHWH to Jesus, reflecting their theological conviction that Jesus shares in the divine identity.

The lack of any manuscript evidence containing the Tetragrammaton or its transliterations in the NT is decisive. While hypothetical scenarios about its inclusion in the autographs can be entertained, they remain speculative and unsupported by evidence. By the time the NT was written, Kyrios was the standard rendering for YHWH in Greek-speaking Jewish and Christian communities. This tradition aligns with the NT authors’ use of Kyrios to emphasize Jesus’ divine status. The NT authors, many of whom came from Jewish backgrounds, adopted the established practice of substituting Kyrios for YHWH in Greek texts. This practice was consistent with the broader theological emphasis on Jesus as Kyrios.

There is no evidence of a transitional phase in which Kyrios replaced the Tetragrammaton in NT manuscripts. The consistent use of Kyrios across all extant manuscripts indicates that this was the original practice. The NT’s consistent use of Kyrios aligns with early Christian theology, which applied Old Testament passages about YHWH to Jesus. This theological emphasis would have made Kyrios the natural choice for NT authors when quoting or alluding to YHWH.

Hurtado does not argue that Kyrios was introduced into the LXX in the second century CE by Christians or otherwise. Instead, he highlights the standardization of scribal practices during this period while acknowledging earlier Jewish use of Kyrios as an oral substitute. The response fails to account for the diversity of renderings for YHWH in early LXX manuscripts and the established use of Kyrios in pre-Christian Jewish contexts. The hypothesis that the Tetragrammaton appeared in the NT autographs is unsupported by any manuscript evidence and contradicts the theological and textual context of early Christianity. The response incorrectly portrays Hurtado’s position as conflicting with Pietersma, Rösel, and others, despite their compatible emphasis on the diversity of early practices and the eventual dominance of Kyrios.