Some other relevant information ....

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a number of people from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. After the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BCE, King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon besieged Jerusalem, resulting in tribute being paid by King Jehoiakim.[1] Jehoiakim refused to pay tribute in Nebuchadnezzar's fourth year, which led to another siege in Nebuchadnezzar's seventh year, culminating with the death of Jehoiakim and the exile to Babylonia of King Jeconiah, his court and many others; Jeconiah's successor Zedekiah and others were exiled in Nebuchadnezzar's eighteenth year; a later deportation occurred in Nebuchadnezzar's twenty-third year. The dates, numbers of deportations, and numbers of deportees given in the biblical accounts vary.[2] These deportations are dated to 597 BCE for the first, with others dated at 587/586 BCE, and 582/581 BCE respectively.[3]

After the fall of Babylon to the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, exiled Judeans were permitted to return to Judah.[4][5] According to the biblical book of Ezra, construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem began around 537 BCE. All these events are considered significant in Jewish history and culture, and had a far-reaching impact on the development of Judaism.

Archaeological studies have revealed that not all of the population of Judah was deported, and that, although Jerusalem was utterly destroyed, other parts of Judah continued to be inhabited during the period of the exile.[6] The return of the exiles was a gradual process rather than a single event, and many of the deportees or their descendants did not return, becoming the ancestors of the Iraqi Jews.

Biblical accounts of the exile[edit]

In the late 7th century BCE, the Kingdom of Judah was a client state of the Assyrian empire. In the last decades of the century, Assyria was overthrown by Babylon, an Assyrian province. Egypt, fearing the sudden rise of the Neo-Babylonian empire, seized control of Assyrian territory up to the Euphrates river in Syria, but Babylon counter-attacked. In the process Josiah, the king of Judah, was killed in a battle with the Egyptians at the Battle of Megiddo (609 BCE).

After the defeat of Pharaoh Necho's army by the Babylonians at Carchemish in 605 BCE, Jehoiakim began paying tribute to Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. Some of the young nobility of Judah were taken to Babylon.

In the following years, the court of Jerusalem was divided into two parties, one supporting Egypt, the other Babylon. After Nebuchadnezzar was defeated in battle in 601 BCE by Egypt, Judah revolted against Babylon, culminating in a three-month siege of Jerusalem beginning in late 598 BCE.[7] Jehoiakim, the king of Judah, died during the siege[8] and was succeeded by his son Jehoiachin (also called Jeconiah) at the age of eighteen.[9] The city fell on 2 Adar (March 16) 597 BCE,[10] and Nebuchadnezzar pillaged Jerusalem and its Temple and took Jeconiah, his court and other prominent citizens (including the prophet Ezekiel) back to Babylon.[11] Jehoiakim's uncle Zedekiah was appointed king in his place, but the exiles in Babylon continued to consider Jeconiah as their Exilarch, or rightful ruler.

Despite warnings by Jeremiah and others of the pro-Babylonian party, Zedekiah revolted against Babylon and entered into an alliance with Pharaoh Hophra. Nebuchadnezzar returned, defeated the Egyptians, and again besieged Jerusalem, resulting in the city's destruction in 587 BCE. Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the city wall and the Temple, together with the houses of the most important citizens. Zedekiah and his sons were captured and the sons were executed in front of Zedekiah, who was then blinded and taken to Babylon with many others (Jer 52:10–11). Judah became a Babylonian province, called Yehud, putting an end to the independent Kingdom of Judah. (Because of the missing years in the Jewish calendar, rabbinic sources place the date of the destruction of the First Temple at 3338 HC (423 BCE)[12] or 3358 HC (403 BCE)).[13]

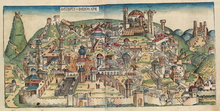

Illustration from the

Nuremberg Chronicle of the destruction of Jerusalem under the Babylonian rule

The first governor appointed by Babylon was Gedaliah, a native Judahite; he encouraged the many Jews who had fled to surrounding countries such as Moab, Ammon and Edom to return, and he took steps to return the country to prosperity. Some time later, a surviving member of the royal family assassinated Gedaliah and his Babylonian advisors, prompting many refugees to seek safety in Egypt. By the end of the second decade of the 6th century, in addition to those who remained in Judah, there were significant Jewish communities in Babylon and in Egypt; this was the beginning of the later numerous Jewish communities living permanently outside Judah in the Jewish Diaspora.

According to the book of Ezra, the Persian Cyrus the Great ended the exile in 538 BCE,[14] the year after he captured Babylon.[15] The exile ended with the return under Zerubbabel the Prince (so-called because he was a descendant of the royal line of David) and Joshua the Priest (a descendant of the line of the former High Priests of the Temple) and their construction of the Second Temple in the period 521–516 BCE.[14]

Archaeological and other non-Biblical evidence[edit]

Nebuchadnezzar's siege of Jerusalem, his capture of King Jeconiah, his appointment of Zedekiah in his place, and the plundering of the city in 597 BCE are corroborated by a passage in the Babylonian Chronicles:[16]:293

In the seventh year, in the month of Kislev, the king of Akkad mustered his troops, marched to the Hatti-land, and encamped against the City of Judah and on the ninth day of the month of Adar he seized the city and captured the king. He appointed there a king of his own choice and taking heavy tribute brought it back to Babylon.

Jehoiachin's Rations Tablets, describing ration orders for a captive King of Judah, identified with King Jeconiah, have been discovered during excavations in Babylon, in the royal archives of Nebuchadnezzar.[17][18] One of the tablets refers to food rations for "Ya’u-kīnu, king of the land of Yahudu" and five royal princes, his sons.[19]

Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonian forces returned in 588/586 BCE and rampaged through Judah, leaving clear archaeological evidence of destruction in many towns and settlements there.[16]:294 Clay ostraca from this period, referred to as the Lachish letters, were discovered during excavations; one, which was probably written to the commander at Lachish from an outlying base, describes how the signal fires from nearby towns were disappearing: "And may (my lord) be apprised that we are watching for the fire signals of Lachish according to all the signs which my lord has given, because we cannot see Azeqah."[20] Archaeological finds from Jerusalem testify that virtually the whole city within the walls was burnt to rubble in 587 BCE and utterly destroyed.[16]:295

Archaeological excavations and surveys have enabled the population of Judah before the Babylonian destruction to be calculated with a high degree of confidence to have been approximately 75,000. Taking the different biblical numbers of exiles at their highest, 20,000, this would mean that at most 25% of the population had been deported to Babylon, with the remaining 75% staying in Judah.[16]:306 Although Jerusalem was destroyed and depopulated, with large parts of the city remaining in ruins for 150 years, numerous other settlements in Judah continued to be inhabited, with no signs of disruption visible in archaeological studies.[16]:307

The Cyrus Cylinder, an ancient tablet on which is written a declaration in the name of Cyrus referring to restoration of temples and repatriation of exiled peoples, has often been taken as corroboration of the authenticity of the biblical decrees attributed to Cyrus,[21] but other scholars point out that the cylinder's text is specific to Babylon and Mesopotamia and makes no mention of Judah or Jerusalem.[21] Professor Lester L. Grabbe asserted that the "alleged decree of Cyrus" regarding Judah, "cannot be considered authentic", but that there was a "general policy of allowing deportees to return and to re-establish cult sites". He also stated that archaeology suggests that the return was a "trickle" taking place over decades, rather than a single event.[22]