Is the King James Version a ‘Roman Catholic Bible’?

by Doug Kutilek

[Reprinted from “As I See It,” 6:2 February 2003]

“It is apparent to any honest person who is not prejudiced or brainwashed by a ‘Christian education’ that all the New Bibles are the Roman Catholic Vulgate of Jerome restored via Westcott and Hort. . . .This is why we say, justifiably and correctly, that the ASV (1901) is a Roman Catholic Bible. . . . A man, Christian or otherwise, has to be as blind as a bat backing in backwards to fail to see that every Bible translated since 1880 is a Roman Catholic Bible, or a Communist Bible.” (Peter S. Ruckman, The Christian’s Handbook of Manuscript Evidence. Palatka, Florida: Pensacola Bible Press, 1970; pp. 155, 156. All italics in original)

On what basis does he make this extraordinary assertion? His basis seems to be, first, that the Roman Catholic Church owns manuscript B, also know as Codex Vaticanus. On the authority of this manuscript, supported by other, frequently extensive evidence, textual changes were made in the “textus receptus” printed Greek text (which generally, but not precisely, is the Greek text behind the King James Version) by more recent printed editions of the Greek New Testament (such as Westcott and Hort). Second, the aforementioned textual changes also often agree with the Latin Vulgate translation of Jerome, the translation that in 1563 at the Council of Trent was declared by the Roman Catholic Church to be “authentical” and the final authority in all theological disputes. Therefore, mere possession of a particular manuscript by the Roman Catholic Church seems to make it a “Roman Catholic” manuscript, and mere recognition or acceptance of a particular translation by the Roman Catholic Church makes that translation a “Roman Catholic” translation. (Other writers, such as David Cloud, editor of O Timothy, would add as further “proof” the presence of Catholic scholar Carlo Martini on the editorial committee for the United Bible Societies’ The Greek New Testament, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th editions; these Greek texts are largely in agreement with the Westcott-Hort text where it differs from the textus receptus).

By extension, it is “reasoned,” any Greek text that agrees with Vaticanus and/or the Vulgate against the textus receptus and/or the King James Version must be a Roman Catholic Bible. And, of course, the mere labeling of something as “Roman Catholic” is deemed sufficient to make it so, and naturally and necessarily discredits it as corrupt (Ruckman is here following the ages-old precept: “If you cannot answer a man’s arguments, all is not lost; you can still call him vile names”). And the presence of a Catholic scholar among the editors of such a Greek text!! “What need have we of further witnesses?” (Some have tried to discredit Westcott and Hort as well by smearing them with claims of Romish inclinations, chiefly through the use of misquotes, half-quotes and misrepresentations. See my article Erasmus, His Greek Text and His Theology posted at www.kjvonly.org).

In truth, a far stronger case can be made, employing this same kind of logic and evidence--and in fact even better logic and more convincing evidence--, that the textus receptus is a Roman Catholic Greek text, and the King James Version is a Roman Catholic Bible translation, while in contrast, revised Greek texts as well as major conservative Bible versions made since 1880 are non-Catholic by virtue of their differences from the textus receptus and KJV. This we shall now demonstrate.

The first printed Greek New Testament was the Greek text found in the Complutesian polyglot, printed in Alcala, Spain in 1514 (though printed first, it was not published, i.e., made available for distribution, until 1522, after the publishing of the first two editions of Erasmus’ Greek text). The Complutesian Greek is definitely in the mainstream of textus receptus editions, and was in fact consulted by Erasmus and formed the basis for some of the revisions he made in the later editions of his Greek text (see F. H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell & Co., 1883. 3rd edition; p. 433). Who edited this text? And on what manuscripts was this edition based?

The editor was Cardinal Archbishop Francisco Ximenez de Cisneros (1436-1517) of Spain. For the uninitiated, his titles indicate that he was near the apex of the priestly hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church in Spain during the very time that the Spanish Inquisition was getting well underway (a brief sketch of his life may be found, among many other sources, in Frank L. Cross, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. London: Oxford University Press, 1957; p. 1482). Where did he obtain manuscripts? At least in part from the Vatican Library in Rome. In the dedication to Pope Leo X of this published work, Cardinal Ximenez stated, “For Greek copies indeed we are indebted to your Holiness, who sent us most kindly from the Apostolic Library very ancient codices, both of the Old and the New Testament; which have aided us very much in this undertaking,” (Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968. 2nd edition; p. 98). So the very first in the line of textus receptus editions, and one which influenced virtually all later ones, was made at the behest of a Catholic Cardinal by Catholic scholars using Catholic-owned Greek manuscripts.

And of course, Erasmus, editor of 5 Greek New Testament editions (1st-1516; 5th-1534) which set the standard for all the later textus receptus editions of Stephanus, Beza and the Elzevirs, was a lifelong Roman Catholic (which some fundamentalist Baptists in flights of pure self-delusion have recently attempted to deny; see my published article, Erasmus, His Greek Text and His Theology noted above). He was ordained as priest and ultimately offered the office of Cardinal (which he refused). Erasmus left in writing his decided opinion that Matthew 6:13; John 7:53-8:11; and I John 5:7 were not original parts of the NT but later scribal insertions (see my above-mentioned article for documentation), opinions shared in common by Westcott and Hort. It is common knowledge that in several places, Erasmus deliberately altered the text he found in Greek manuscripts and fabricated readings based solely on the Latin Vulgate! One among several such places is Acts 9:5,6; also the last 6 verses of Revelation were entirely Erasmus’ back translation from Latin into Greek, since his one Greek manuscript completely lacked these verses. Erasmus the Catholic was sole editor of his various NT editions; therefore his Greek NTs can honestly and accurately be called Catholic Greek texts. The presence of just one Catholic scholar on the editorial committee of the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament is hardly noteworthy by comparison.

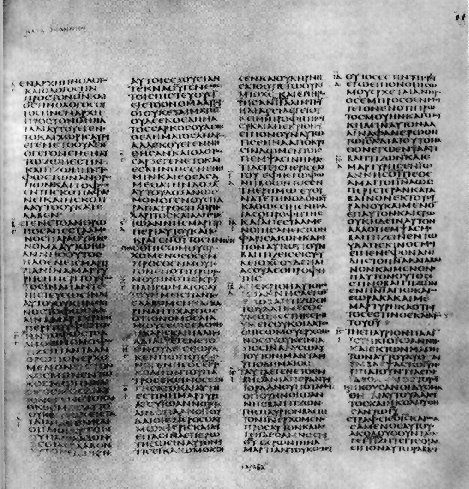

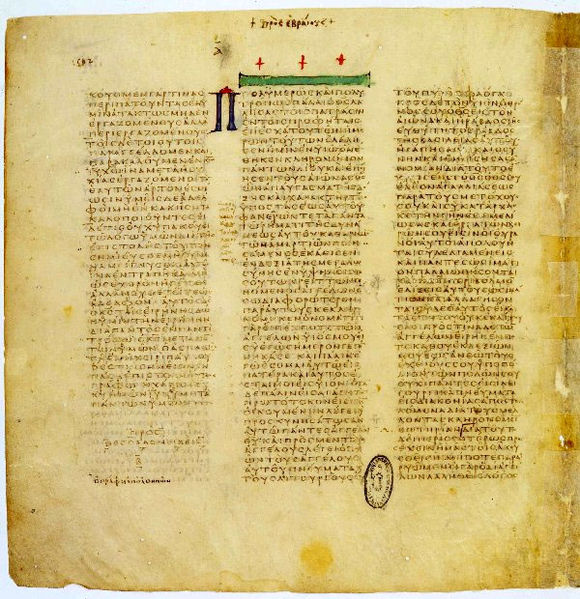

And, incidentally, Ruckman has failed to show how the mere possession of Codex Vaticanus (Manuscript B) by the Vatican makes it a Roman Catholic manuscript. It is all but universally acknowledged that this manuscript dates to the first half of the 4th century (340 A.D. is a commonly given date). This means it pre-dates the Vulgate, and really pre-dates the rise of the Roman Catholic Church which did not exist in anything like its present domineering hierarchical form until centuries later. Furthermore, though the Vatican Library currently owns Vaticanus and has at least since 1475 (or 1481, according to Frederick Kenyon, Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament. London: Macmillan, 1901; p. 63) when the first catalogue of manuscripts in that library was made, yet it seems probable that this manuscript had been in the possession of the Greek Orthodox Church--the guardians and propagators of the Byzantine text type--until 1453 when the Turks took Constantinople, and the resident scholars fled west with their valuable manuscripts, Vaticanus perhaps among them.

(Another minor “proof” of the “Catholic” nature of Manuscript B, at least according to Ruckman, is the fact that the manuscript is defective after Hebrews 9:14, thereby dropping “the chapter in Hebrews that deals with the one, eternal, effectual sacrifice of Jesus Christ which did away with the ‘sacraments!’ “ (Peter S. Ruckman, The Christian’s Handbook of Manuscript Evidence, p. 71; all emphasis in original). This claim as “evidence” is exposed as bogus by the fact that the lacuna in Hebrews--and the rest of the New Testament now lost from this manuscript as originally written--was replaced from another manuscript in the 15th century, meaning that the chapter in Hebrews in question is currently and for over 500 years has been included in this manuscript, with no attempt to “suppress” this passage. And besides, the passage has always been present in the Vulgate, Rome’s official Bible, so no motive of deliberate corruption of the text can be honestly discerned. Ruckman is here throwing dust in the air just to obscure the issue.

And then there is his outrageous claim--based on nothing more than his abysmal ignorance of the facts--that “no Protestant scholar has ever handled” Vaticanus (ibid., p. 6). The deduction Ruckman wants his gullible reader to make is that there is something very sinister afoot when it comes to this manuscript. I exposed the erroneous nature of Ruckman’s claim in my article Ruckmanism: A Foundation of Sand, also posted at www.kjvonly.org wherein I showed that among others, this manuscript had been personally examined--well more than a century before Ruckman wrote--by such Protestant scholars as Alford, Tregelles, Tischendorf, and even Burgon.)

Further, if mere possession by Rome makes a manuscript corrupt (“guilt by association”), then the many Byzantine--majority or traditional text--manuscripts housed at the Vatican are therefore likewise tainted (and for a brief and surely incomplete listing of Greek NT manuscripts now in Rome, see Alexander Souter, ed., Novum Testamentum Graece. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1947. 2nd edition, pp. x-xviii where some 25 manuscripts are noted as being currently in Rome).

And what shall we say in this regard concerning the Sinaiticus manuscript, designated Aleph? Like Vaticanus a chief witness to the Alexandrian text-type, it was long in the possession of St. Catherine’s monastery--a Greek Orthodox monastery--and is currently in the possession of the British Museum. The Greek Orthodox Church--in spite of doctrines very little different in essence from Roman Catholicism, must be deemed among the “good guys” by Ruckman since it preserved the Byzantine text, from which, generally (but only generally) speaking, the KJV was made (and of course anything connected with or agreeing with the KJV is “good” and anything differing from it is “bad”; the first and all-encompassing assumption of KJVOism which trumps all contrary evidence and reason is that the KJV is “the Word of God preserved in the form we should have it”). And since the British Museum is a government institution of the United Kingdom, where the Church of England is the official, established state church--and the very institution that carried out the translation of the King James Version--then the Sinaiticus must be “innocent by association,” n’est-ce pas? The whole line of argument, is of course invalid. Vaticanus stands or falls on its own merits, not on the basis of who currently possesses it.

In the period from the latter 17th century to the middle of the 19th century, Protestant scholars like John Mill, Richard Bentley, J. A. Bengel, J. J. Wettstein, J.J. Griesbach, Karl Lachmann, S. P. Tregelles, Constantine Tischendorf and B. F. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort were either compiling lists of variant readings from Greek manuscripts and other witnesses with an aim of revising the textus receptus, or were actually publishing such revised texts based on evidence from those ancient witnesses. However, at least one scholar was at work in this period creating a text that moved back toward the textus receptus, and away from the revised text of Griesbach, the first to publish a text that abandoned the textus receptus. That scholar was J. M. A. Scholz (1794-1852), a Roman Catholic (see Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968. 2nd edition; pp. 123-4).

Briefly stated, then, the movement away from the textus receptus, which had been edited by Roman Catholic priest Erasmus, and toward the critical text was the work of Protestant scholars. The critical text may indeed be characterized as a non-Catholic Protestant text! Strange that modern English versions based on it could be characterized as “Catholic” translations. (Such inconsistency is also evident in the KJVOnly movement’s embracing of certain medieval versions as sound--Wycliffe’s version and the Waldensian Bible among them--though these were translated directly and solely from the Latin Vulgate text).

And then what can be said about what are reportedly the virtually Roman Catholic views of King James I, royal patron of the KJV and the one who imposed the rules on the team of translators? “Roman Catholic views of King James?” you ask incredulously? Yes. Consider the remarks of famous 18th century Anglican pastor and hymn-writer Augustus Toplady (1740-1778), author of “Rock of Ages” and other hymns. Toplady tells us that James I made “enormous concessions to the Church of Rome.” “It has ever been my way, said James, to go with the Church of Rome, usque ad aras [Latin, literally, “to the very altars,” i.e., to the last extremity]: i.e., to symbolize with the Church in matters of doctrine, discipline and worship, as far as prudence would permit and policy might require. Indeed, the papal supremacy over kings themselves, and the lawfulness of king killing seem to have been the only Popish doctrines which he considered indigestible.” (August Toplady, The Works of Augustus Toplady. London: J. Chidley, 1837, p. 247). Was there any similar Romish patronage of the NIV or NASB or NKJB? I trow not.

And then there is the connection of the KJV with the Roman Catholic Rheims translation. The Rheims (English) New Testament was first published in 1582, and was the work of English Catholic scholars-in-exile living in France (the corresponding Douay Old Testament, not published until 1610, is not relevant to our discussion here, and so will be ignored). The production of this translation was not motivated by a zeal to put the Word of God into the language of the English-speaking people so that they could read it for themselves, but as a defensive move against the extant and ever-increasing number of English Protestant Bible versions. Since the Romanists could not prevent or control the distribution of English Bible versions in England, they produced their own so that by translation and annotation they might enforce and defend Catholic doctrine, and thereby give English Catholics a Bible to read--if they must!--that might not lead them to the full light of Protestantism. And rather than being translated directly from the Greek as had all English NTs since Tyndale’s first edition (1526), this version was made directly from the Latin Vulgate version (which the Roman Catholic Council of Trent just a couple of decades earlier had declared “authentical”), though Greek texts and other versions were also consulted in the translation process.

King James I in his instructions to the translators had granted them the expressed right to make use of several earlier English translations--the Bishops’ Bible as their base text, to be revised in consultation with the versions of Tyndale, Coverdale, Matthew, Whitchurch, and the Geneva Bible. The King’s list--the King’s direct instructions--nowhere lists the Rheims New Testament. Nevertheless, the translators of the KJV NT unmistakably used the Rheims NT throughout their revision work; the wording and phraseology of the Rheims NT having left its mark on the KJV in literally thousands of places.

And may I indulge in an aside here? One of the issues over which Anglican priest Dean John William Burgon in his excessively vehement denunciations of the English Revised New Testament of 1881 castigated that translation committee was that they did not strictly follow the rules laid out for them (and indeed in some matters, they did not). Of course, the good Dean (and his fawning present-day admirers) was deathly silent over the KJV translators’ manifest disobedience to the King’s expressed translation guidelines. And it was not merely another English version outside the King’s list which the KJV men employed, but a Catholic one, one translated from the Latin, not the original Greek!

Burgon also vociferously denounced the inclusion of non-Anglican scholars on the ERV translation committee, among them Baptists, Methodists and other non-Conformists. He very much thought that the Revision, like the KJV itself, should be made entirely by those within the camp of the Church of England. Let us not forget that the Church of England, unlike other Protestant denominations (Lutheran, Reformed, etc.), began solely over matters of practice, not doctrine. King Henry VIII of England wanted a divorce from his wife Catherine of Aragon; the Pope refused. So, Henry VIII split with Rome, declared himself head of the Church of England and had the Archbishop of Canterbury grant him his desired divorce.

Official doctrine of the Church of England at the time of the making of the KJV differed little from that of Romanism and included infant baptism, baptismal regeneration, union of church and state, persecution of dissent, denial of salvation outside the church, and much else--all in agreement with Rome, and all utterly hateful to those fundamental Baptists who embrace exclusively the KJV today. According to Henry Jessey (1601-1663), a Baptist pastor in London who prepared a complete revision of the KJV which was left in manuscript at his death (on which see my article, “Earliest Baptist Revision of the KJV: 1614,” Baptist Biblical Heritage 2:1), reported that in the KJV, in at least 14 places, the language of the translators was altered by George Abbott, Archbishop of Canterbury, to conform to the teachings of “prelacy,” that is, the highly centralized episcopal form of church government adhered to by the Church of England (see Christopher Anderson, The Annals of the English Bible. London: William Pickering, 1845. vol. II, p. 378). In short, the KJV translation was deliberately falsified to conform to a form of church government not differing markedly (save for subjection to the pope) from that of Romanism.

But perhaps the most definitive “proof” that the KJV is in fact a “Catholic Bible” is the undeniable use by the translators of the Roman Catholic Rheims NT. The translators of the 1881 ERV NT were frank about the KJV’s use of the Rheims NT. They said in their “Preface” to the New Testament that the text of the KJV “shows evident traces of the influence of a Version not specified in the rules, the Rhemish, made from the Latin Vulgate, but by scholars conversant with the Greek original.” (p. VI). And indeed this influence is pervasive. Dr. J. G. Carleton in his work The Part of Rheims in the Making of the English Bible (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1902. 259 pp.) has shown that the KJV has taken some 2,803 readings, besides 140 marginal readings--nearly 3,000 in all--from the Roman Catholic (Rheims) translation of 1582 (Carleton’s book was first brought to my attention by Lemuel J. Hopkins-James in his The Celtic Gospels: Their Story and Their Text by. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934; reprint 2001, p. xx). After a brief but helpful survey of English Bible versions before 1611, Carleton explains his methodology, and then presents his findings in extended lists, meticulously prepared, showing precisely where and how the KJV was influenced in its vocabulary, phraseology and grammar by the Roman Catholic Rheims NT, an influence that literally affects every page of the KJV NT.

Consider two summary statements by Carleton: “The Tables annexed give the sum total of the issue of my inquiry. They speak for themselves as to the intimate relationship, hitherto insufficiently acknowledged, which exists between the Authorized and Rhemish Versions. If one were to assess the degree of obligation due from the former to the latter, it might, I think, fairly be said, that while the Translation of 1611 in its general framework and language is essentially the daughter of the Bishops’ Bible, which in its turn had inherited the nature and lineaments of the noble line of English versions issuing from the parent stock of Tyndale’s, yet with respect to the distinctive touches which the Authorized New Testament has derived from the earlier translations, her debt to Roman Catholic Rheims is hardly inferior to her debt to puritan Geneva,” (p. 31). And again, “As a set-off against these improvements, in which A[uthorized] has followed R[heims], we observe instances, not a few, in which A[uthorized] has been led by R[heims] into translations distinctly inferior to the earlier renderings, to which the Revised Version has frequently returned,” (p. 53).

Before I became aware of Carleton’s book, I did some comparisons of the KJV and Rheims myself. In the brief book of James, I found 32 places where the KJV text exactly reproduces the wording of the Rheims translation against all previous English versions, another place where the wording of the Rheims is in the KJV margin, plus an additional 7 places where the KJV closely approximates the Rheims, for a total of 40 places in 5 chapters, and I am not certain that I found all such places. I Peter chapter 1 alone yields 19 such places.

Let the reader who doubts the pervasive impact of the Catholic Rheims NT on the KJV NT--who doubts because he cannot bring himself to face these facts--secure Carleton’s volume for himself, and see with his own eyes.

Should we not find this revelation stunning, even appalling-that the KJV NT in nearly 3,000 places indeed is a “Catholic Bible” that is, it reproduces wording borrowed directly from, and only from, the first Roman Catholic translation of the NT into English. And of course there are thousands of other places where the wording of the KJV agrees exactly with the Rheims NT where it in turn happens to agree with some one or more of the earlier English versions also consulted by the KJV translators.

And then there is the fact of strong and repeated influence of Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translation on the King James Version, besides the influence of the Rheims NT. F. H. A. Scrivener, in his extensive study of the KJV (and Scrivener was universally recognized as the greatest 19th century expert on the KJV in its various editions) determined that in the NT, the KJV most closely follows the 1598 Beza Greek text. In about 190 places, though, the KJV NT abandons the reading of that edition for some other and earlier printed Greek text. In at least 60 additional places (a figure Scrivener grants as being likely well below the actual number), the KJV NT follows the reading of NO then-existing printed Greek text, but instead exactly follows the reading of the Latin Vulgate--“In some places the Authorised Version corresponds but loosely with any form of the Greek original, while it exactly follows the Latin Vulgate,” (F. H. A. Scrivener, The New Testament in Greek according to the Text Followed in the Authorized Version. Cambridge: University Press, 1881; p. ix. The appendix on pp. 655-6 gives a list of the places corresponding exactly with the Latin Vulgate against the Greek).

Not only in occasionally following the Vulgate text against the Greek, but in the very translation itself, the KJV shows the definite and widespread influence of the Latin Vulgate version. W.E. Plater and H. J. White point out that the very vocabulary of the KJV is fraught with words lifted directly from the Vulgate, noting among a multitude of possible examples such words as “publican,” “Calvary,” and “charity,” (A Grammar of the Vulgate. New York: Oxford University Press, 1926; p. 4). They also take particular note of how the KJV has been adversely influenced by the Vulgate with regard to the translation of the Greek definite article. The Latin language, having no definite article, cannot convey the force of the Greek article. As a result, translators closely familiar with the Vulgate and influenced by it, as the KJV translators individually and collectively were, failed frequently to convey into English the force of the Greek definite article (pp. 76-8; Plater and White list numerous specific examples in the KJV).

And then there is the somewhat embarrassing fact that the original 1611 KJV included the Apocrypha (as did all editions of the KJV for decades after 1611, and as did most editions until about 1800). The 13 books called collectively the Apocrypha were declared canonical by the Roman Catholic Church at the Council of Trent in the 16th century A.D., even though they were excluded from the OT canon recognized anciently by the Jews, by Jesus and the Apostles, by many of the church fathers (including Origen and Jerome) and by all Reformation-era Protestants. Yes, the Apocryphal books are inserted between the Testaments in the 1611 KJV (as in Greek Orthodox Bibles; the Greek Orthodox Church accepts these books as canonical), but they are still very much present. In contrast, consider the fact that in Bible translations which Ruckman labels “Catholic,” the Apocrypha is entirely absent. This is true of the ASV, NASB, NIV, and NKJB. In this regard, who follows Catholic practice more closely? Surely it is the KJV!

So, were we indicting the KJV for being a “Roman Catholic Bible,” we would be compelled to recognize these facts: that it was 1. a translation sponsored by a king who was in nearly all doctrinal points in agreement with Rome; 2. a translation made by Anglicans whose official doctrine is far closer to Romanism than to Fundamentalism; 2. a translation based largely on a Greek text compiled by a Catholic priest, a text wherein he falsified readings on the basis of the Latin Vulgate; 3. a translation which in turn abandoned that Greek text so as to conform yet more closely to the Vulgate in at least 60 places; 4. a translation which very often adopted the exact vocabulary of the Vulgate and was not a few times led astray by its grammar; 5. a translation evidencing the continuous influence--nearly 3,000 specific places in all--, of a Roman Catholic English translation, one not even included by the king in his instructions to the translators; and 6. a translation that included the Apocrypha between the Testaments. In all these things, the KJV is wide open to the charge of being a Roman Catholic translation to a far greater degree than anything that could be imagined regarding the NASB, NIV or NKJB.

If the KJVOers were rabid NIVOers instead, they would eagerly seize on these arguments to prove that the KJV was a Catholic Bible. Indeed, all these arguments would readily serve if one were of a mind to make such a claim.

The thing is done. Ruckman and his acolytes are discredited by the very arguments they employ. How I wish that KJVO zealots were actually open to hear evidence and were truly interested in facts and reason, instead of merely seeking to bolster their presuppositions by any argument, however fraudulent or ill-considered, that can be fabricated.

But I fear I hope too much.

---Doug Kutilek

PRINTER VERSION