@Earnest

I quote from HERE:

The Watchtower's final defense is that a handful of other translations and the Curetonian Syriac also place "today" with "Amen I say to you" and not the following expression. It must first be stressed this argument from authority does not prove that the comma is misplaced in the majority of translations. The NWT may not be unique in its punctuation of this verse, but that fact does not establish its correctness.

The two English versions mentioned by the Watchtower are Rotherham and Lamsa. Rotherham's translation of Luke 23:43 may well be influenced by E.W. Bullinger, whom Rotherham knew and respected (Reminiscenses of JB Rotherham, Chapter 10.). Whether Bullinger's views were well-founded will be examined later in this essay. In any event, Rotherham's translation has not been recognized by Bible scholars of any theological persuasion as being authoritative. The translation of George Lamsa may have once been punctuated as the WT claims, but all editions I have seen place the comma in the traditional location. Furthermore, if Lamsa's Aramaic source was the Peshitta (Bruce Metzger expressed some doubt on this point*), the English translations of the Peshitta by James Murdock and J.W. Etheridge also place the comma before "Today."

- * George Lamsa, L-A-M-S-A, who in the 1940s persuaded a reputable publisher of the Bible in Philadelphia, the Winston Publishing Company, to issue his absolute fraud, of 'the Bible translated from the original Aramaic.' Absolutely a money getter, and nothing else. He said that 'the whole of the New Testament was written in Aramaic,' and he 'translates it from the Aramaic,' but he never would show anybody the manuscripts that he translated from. Secondly, why would Paul write in Aramaic, let us say, to the people of Galatia? They didn't know any more Aramaic than people in Charlestown or Princeton know Aramaic.�

- The Curetonian Syriac

Regarding the Curetonian Syriac, it is true that it places "today" with "Amen I tell you," but it is problematic to use this fact in support of a correct understanding of the original Greek text. The Old Syriac Gospels are preserved in two manuscripts: The Sinaitic and the Curetonian. Both contain Luke 23:43. The Sinaitic most likely predates the Curetonian by about 100 years. Burkitt posits that the Sinaitic represents a more accurate Syriac text, while the Curetonian was corrected from a later Greek text (one containing a number of spurious passages) (Burkitt, Crawford, Evangelion Da-Mepharreshe, Vol 2, Gorgias Press, 2003.). Luke 23:43 in the Sinaitic text reads:

Jesus said unto him, Verily I say unto thee, To day shalt thou be with me in Paradise."7

The Syriac Peshitta agrees with the Sinaitic text, against the Curetonian, as do the Syriac Diatessaron, the Sahidic Coptic, and a number of manuscripts of the Old Latin. Ephrem, a 4th century commentator on the Syriac Gospels, quotes this verse three times, each time omitting "today." However, he says, "Our Lord shortened His distant liberalities and gave a near promise, To-day and not at the End....Thus through a robber was Paradise opened." (Burkitt, op cit., p. 304. Burkitt also quotes Barsalibi (d. 1171) who admits that "some" place "today" with "Amen I tell you," but does not approve of this reading.)

The Curetonian manuscript is thus of no value in determining the correct punctuation of Luke 23:43. It cannot be demonstrated that its reading was regarded as normative within the Syriac gospel tradition. More importantly, its connection to a Greek original cannot be established. The most that can be said is that a Syriac translator or corrector rendered the verse in a way similar to the NWT. It has not been established that this rendering is accurate. The evidence we have suggests that it was not. As Syriac Gospel scholar P.J. Williams writes:

"While the Greek may have been ambiguous, overwhelmingly ancient interpreters chose the opposite interpretation to that of the Watchtower" (P.J. Williams, PhD, private email to Robert Hommel, dated 1/6/2005.).

objection: Witness apologist Greg Stafford offers a number of arguments in favor of the NWT punctuation of Luke 23:43.

Codex Vaticanus

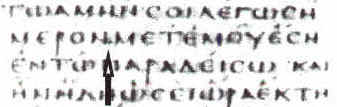

His first is that a major early manuscript of the New Testatment contains a punctuation mark - equivalent to a comma - after "today," just as does the NWT:

While punctuation in NT manuscripts of the first few centuries CE is not common, one of the best, if not the best witness to the text of the NT, Codex B or Vaticanus (Vatican 1209) of the fourth century CE, does have a mark of punctuation in Luke 23:43; the punctuation is not after �I say� but after the Greek word s�meron, �today" (Stafford, pp. 546-547).

Stafford says that a Vatican Library scholar verified by letter that the mark in question does not appear to be by a later copyist, due to the color of the ink. Mr. Stafford concludes that it dates from the 4th century and therefore offers textual support for the NWT punctuation from a reliable ancient Greek manuscript. Stafford, p. 547. Mr. Stafford does not quote the letter directly. He says simply that in response to "several questions regarding the punctuation of Luke 23:43," the Vatican scholar replied that the dot was "faded brown" and had not been traced over by the later copyist. Mr. Stafford does not name the author of the letter nor provide his qualifications as a textual critic, identifying him only as a "Patristics scholar." Importantly, it is Mr. Stafford's conclusion that the dot is an intentional punctuation mark dating from the 4th century, not the anonymous scholar's (at least, Mr. Stafford does not quote him as saying so).

Mr. Stafford is here responding to Dr. Julius Mantey, who in his famous letter to the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, writes the following:

Why the attempt to deliberately deceive people by mispunctuation by placing a comma after "today" in Luke 23:43 when in the Greek, Latin, German and all English translations except yours, even in the Greek in your KIT, the comma occurs after leg� (I say)..."

Mr. Stafford concludes: "Of course, while this [the comma in Codex B] does not prove anything regarding Luke's original text, it certainly disproves Mantey's claim that Greek manuscripts do not support the NWT's punctuation of Luke 23:43" (Stafford, p. 548). It is debatable whether Dr. Mantey was referring to ancient Greek manuscripts (he specifically writes "translations"); but in any event, Mr. Stafford's assertion (stated negatively) is that the dot in Codex B is an intentional punctuation mark, dating from the 4th Century, and that it supports the NWT.

Response: It is not at all clear that the dot in Codex B is an intentional mark of punctuation. It may nothing more than a dot or an accidental inkblot.

|  |

An 'accidental' inkblot or dot in Codex Vaticanus. The blot appears between the rho and kappa in sarkos ("flesh") in Romans 9:8. | The Watchtower's published image of the alleged low-point punctuation in Luke 23:43, Codex Vaticanus. |

If the dot is, indeed, an intentional mark of punctuation, it is almost certainly not by the original hand. "The point at the top of the line (�) (stigmh teleia, 'high point') was a full stop; that on the line (.) (upostigmh) was equal to our semicolon, while a middle point (stigmh mesh) was equivalent to our comma. But gradually changes came over these stops till the top point was equal to our colon, the bottom point became a full stop, and the middle point vanished, and about the ninth century A.D. the comma (,) took its place" (Robertson, Grammar, p. 242).The original scribe did not use the "low-point" dot, and when using punctuation (which he did rarely), he typically added an extra space, which is not the case here.

Typical spacing added after a mark of punctuation in Codex Vaticanus (between Luke 22:30 and 22:31)

Further, if the scribe intended to place a comma after s�meron, he would probably have used a middle-point as he did after sarka in Romans 9:5 (and various other places), not the low-point, which was more or less equivalent to our semi-colon. However, punctuation in early manuscripts, and particularly in Codex Vaticanus, was far from consistent. So, we must concede this it is possible that a scribe or corrector might use a low-point in a manner consistent with our modern comma; however, given the fact that the low-point does not appear to have been used at all by the 4th century scribe or his contemporary corrector, while they did (rarely) employ both the high-point and middle-point, it would seem most unlikely that one of them did so here. Robertson says: "B has the higher point as a period, and the lower point for a shorter pause" (Ibid.). However, Robertson does not say the "lower point" was by the original scribe or his 4th Century corrector.

Finally, to my knowledge, no commentators or textual critics have mentioned the alleged comma in Vaticanus. Bruce Metzger, in his Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, says nothing of it, even though he addresses the Curetonian Syraic (see above) in relation to the correct punctuation of Luke 23:43, and discusses the punctuation mark in Vaticanus at Romans 9:5. Metzger, p. 155 (c.f., pp. 459 - 462). As I was preparing this article, I corresponded briefly with Dr.Wieland Willker about the alleged comma in Vaticanus. Dr. Willker has a webpage dedicated to Codex Vaticanus and an online Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels. As a result of our correspondence, Dr. Willker added information about the dot in Vaticanus to the third edition of his Commentary. Dr. Willker agrees that the dot is "of unknown origin," and is not by the original scribe. He concludes:

The dot in B is not of much relevance because the punctuation question exists independent of it. The punctuation, if there was any at all, was, like spelling, irregular in the early MSS. Any punctuation in ancient MSS is VERY doubtful. The punctuation in Nestle-Aland or GNT is NEVER based on a punctuation in a MS. It is ALWAYS a decision based on grammar, syntax, linguistics, and exegesis (Willker, Textual Commentary, p. 436, emphasis in original).

Dr. Willker lists the following manuscripts which place hoti after leg�, thus emphasizing that "today" modifies "you will be with me...": L, 892, L1627, b, c, Co, and Sy-S. He lists AM 118 PS8, 11(1.8), Apo, and Hil as manuscripts that do the same thing with different syntax. He also lists several sources supporting a comma after "Today," but these all are from a posting on the B-Greek discussion list, each of which are examined later in this article.

The Vaticanus manuscript was originally written in the fourth century in brown ink, with a corrector soon thereafter making some slight changes. Then, a later scribe in the tenth or eleventh century traced over the lettering in black ink, skipping those letters or marks he thought to be incorrect, and making some additional changes ( Finegan, pp. 127-28.). As noted, Mr. Stafford (citing a letter from a Vatican Library scholar) says the dot is "faded brown" and concludes that it dates from the fourth century and not from the later medieval copyist. While the color may indicate an early date for the dot, this is not certain. Even if it is, it has not been established that it is from the original hand or the 4th century corrector, and the fact that it was not reinforced by the later corrector indicates that he regarded it as unintentional or in error. Dr. Peter M. Head, a specialist in NT manuscripts, writes:

I don't think it is punctuation. Certainly not in the original scribal production: there is nothing else like it on the whole opening (punctuation in Vaticanus is almost entirely only by spacing), it doesn't look like a dot, more like a blemish or as you said, a blot; and the spacing is all wrong for punctuation by the original scribe. I suppose it could be added later by someone wanting to repunctuate the text, but even so I'm not persuaded that the colour is the same as the other material introduced by the enhancer/accenter, so you have to attribute it to an unknown reader/punctuator. [Peter M. Head, PhD, personal email to Robert Hommel, dated 1/11/2005. Larry W. Hurtado, PhD, also suspects that the mark is a blot or blemish and not a mark of punctuation (personal email to Robert Hommel, dated 1/5/2005).]

Therefore, the most that can be said is that if the dot is intentional punctuation, it was not copied from an earlier exemplar by the original scribe, but was introduced - for an unknown reason - by an unknown hand at an uncertain time. This would seem thin evidence, indeed, of a textual tradition in the Greek manuscripts dating from the 4th century, as Mr. Stafford proposes.

But what if it could be established that the mark is intentional and dates from the 4th century (as unlikely as that seems) - does it then provide early support for the NWT punctuation? Yes and no. It would provide evidence apart from the Curetonian Syriac that someone long ago, due to the ambiguity of the Greek, understood (or misunderstood) the verse as the Watchtower does. But it would prove nothing with regard to what Luke intended. Mr. Stafford admits as much: "While this [a punctuation mark dating from the 4th century] does not prove anything regarding Luke's original text, it certainly disproves Mantey's claim that Greek manuscripts do not support the NWT's punctuation of Luke 23:43" (Stafford, p. 548, emphasis in original). Of course, this evidence only "certainly disproves Mantey" if a) Mantey meant "manuscripts" when he wrote "translations"; b) that the dot is an intentional punctuation mark and not an accidental blot; and c) that it actually dates from the 4th century. The textual scholars who punctuate our authoritative Greek New Testaments do not do so on the basis of punctuation in ancient manuscripts:

The presence of marks of punctuation in early manuscripts of the New Testament is so sporadic and haphazard that one cannot infer with confidence the construction given by the punctuator to the passage. (Metzger, p. 460, n. 2.)

Thus, even granting Mr. Stafford his argument, the presence of a punctuation mark (if such it is) in one early manuscript tells us nothing about how to properly punctuate Luke 23:43. The correct punctuation is a matter of exegesis, not of textual criticism.

Layton's translation

of the Sahidic Coptic is not authoritative proof that the

comma should follow "today." His interpretation represents a minority

view and is not reflective of the broader consensus among Coptic scholars. Most

translations of the Sahidic Coptic, such as those by Lambdin and Horner, place

the comma before "today," aligning with traditional Christian

doctrine. The Coptic text structure follows the same ambiguity as the Greek but

is generally understood to support the traditional punctuation. Layton’s

rendering is an interpretive decision, not a direct reflection

of the grammatical rules.

The Curetonian Syriac is

indeed one of two Old Syriac manuscripts. However, it does not outweigh

the testimony of the Sinaitic Syriac, which predates it and agrees with the

traditional punctuation. Syriac Peshitta, the standard and

widely accepted Syriac text, supports the traditional reading. Even early

Syriac commentators, like Ephrem the Syrian, interpret the verse as promising

immediate entry into Paradise upon death. The Curetonian Syriac represents a minority

textual tradition, and its divergence from the mainstream Syriac text

diminishes its weight as evidence. According to Bruce M. Metzger, the majority

of ancient Bible translations also follow the majority view, with only

the Aramaic language Curetonian Gospels offering significant testimony to the

minority view.

The hypostigme

(low dot) in Vaticanus is not a reliable indication of punctuation. It could be

an ink blot, a scribal error, or an idiosyncratic mark

introduced by a later hand. Punctuation in early Greek manuscripts was

inconsistent and rarely definitive. Notably, textual scholars

like Metzger and Willker have dismissed the Vaticanus dot as irrelevant. Even

if it were intentional, it reflects one scribe's interpretation,

not a broader textual tradition. Vaticanus' alleged punctuation does not establish

the NWT reading. Punctuation in ancient manuscripts does not carry the same

interpretive authority as grammatical structure and broader textual evidence.

The phrase

"Truly I say to you" (Ἀμὴν λέγω σοι) occurs nearly 70

times in the New Testament, and never is

"today" connected with "I say to you." Instead, the content

of the statement follows immediately.The JW interpretation would require the

phrase to read something like "Truly I say today to you"

(Ἀμὴν σήμερον λέγω σοι), but this is not the Greek structure. Greek

syntax places "today" with the subsequent clause:

"You will be with me in Paradise." The overwhelming grammatical

evidence places "today" with "You will be with me in

Paradise," making the NWT reading linguistically improbable.

While early Greek

manuscripts did lack consistent punctuation, the context and parallels

within Scripture support the traditional reading. The overwhelming consensus of

ancient manuscripts (Greek, Latin, Syriac, and Coptic) aligns with the

traditional interpretation. Translations like the Old Latin, Vulgate,

and Peshitta universally render the verse as, "Truly, I

say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise." The consistency of

traditional punctuation across ancient translations demonstrates a strong

textual tradition contrary to the NWT rendering.

The immediate promise of

Paradise aligns with Christ’s teaching about the soul's survival after death

(e.g., Luke 16:19–31, Matthew 22:31–32). The thief’s body would die, but his

soul would be in Paradise with Christ that day. Paul’s writings reinforce the

belief in immediate fellowship with Christ upon death: “To be absent from

the body is to be present with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8). This

contradicts the Jehovah’s Witness teaching of "soul sleep." The

traditional reading is consistent with biblical theology regarding the state of

the soul after death, while the NWT rendering imposes doctrinal presuppositions

on the text.

The NWT translation

reflects the theological presupposition that the soul ceases to exist at death.

This is not supported by the majority of ancient texts or Christian doctrine. Even

in cases where translations differ slightly (e.g., Rotherham), the broader

consensus among scholars, early Church Fathers, and textual traditions

overwhelmingly supports the traditional reading. The NWT punctuation reflects theological

bias rather than fidelity to the Greek text or historical

interpretation.

Check THIS too.